Landscape and perception: towards a sensitive exploration of territory

Definitely, landscape is an experience; it is the confrontation of a person before an open space and towards a multitude of stimuli that make him or her not only see, but to appreciate the landscape with all the senses.

Since immemorial times human beings have maintained a sensitive relation with the territory. Rivers, mountains, forests, caves, the sea… all these natural elements constituted not only spatial references that helped human groups to recognize the space they crossed, but they quickly became entities with strong significance.

At that time, the lives of humans and animals were governed almost exclusively by the rhythms of seasons and natural cycles.

Landscape of Gran Sabana, on the trail that leads to Roraima Mt.

Photography: Paolo Costa Baldi, 2010. Wikicommons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gran_Sabana_paisaje_1.jpg

According to Italian theorist Francesco Careri 1, the fact of walking became a symbolic action that allowed man to inhabit the world. Through this activity, the human being began to build and to understand the surrounding landscape, as well as to construct categories with which he interpreted his surroundings.

Careri explains how the social division between nomadism and sedentarism brought consequences to the way of perceiving and inhabiting space 2: for centuries different societies developed settlements with a dual logic that included building and travel through space, materialized in buildings and streets.

Later the author explains how the first monuments or spatial references were created throug “menhirs” 3, elements erected by the human being for religious or astronomical purposes 4.

The Menhir de Champ-Dolent, largest menhir in Brittany, France (Size 10 m).

Photography: (Guillaume Piolle). 2010. Wikicommons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Menhir_du_Champ_Dolent.jpg

Similarly, human territories were gradually transformed by roads and travels, which usually were made for trading and migration (not for pleasure as many of us conceive nowadays).

According to Leed Erich, in Germany the relationship between experience and displacement is deeply rooted in linguistics: the word irfaran, which means “experience” in ancient German, also means to travel, to leave, to cross or to wander.

It is worth mentioning that in the Middle Ages or pre-Columbian times in America, the journey was a hard and risky activity that tested and perfected the character of the traveler.

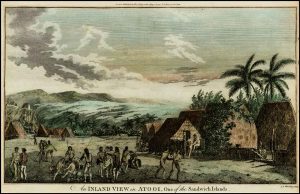

A hand-coloured lithograph depicting a village visited by Captain James Cook near Waimea, Kauai, on his third voyage. Based on a 1778 etching by John Webber which was published by William Hodges, it is one of the few views of Hawaii made during Cook’s third voyage (1776–1779).

Photography: Wikicommons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:An_Inland_View_in_Atooi,_One_of_the_Sandwich_Islands_(1785).jpg

According to historian Marc Desportes 5, in the history of mankind the different means of transport between cities have served as mediators between man and landscape, ultimately affecting his perception and interpretation.

In this way, the author tells us how the landscape of carriage travel was replaced in the nineteenth century by trains, and later in the twentieth century by car, fast train and plane.

It is possible that one of the first evidences of the perception of the speed in the displacement during ends of 19th century and principles of the 20th was translated to art, for example, the pointillism or the fragments traces of the impressionist French painters and with the representation of the movement in the art of futurists 6.

Detail of The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train, by Claude Monet (1877). Harvard Art Museums.

Photography: Google Arts & Culture, https://www.dropbox.com/s/igei05twz12v20u/Detalle.jpg?dl=0

Speed is definitely a mechanism by which the landscape is inevitably abstracted. Who has not gone in a car and overlooked a traffic sign or even forget to turn into a street? The more quickly we move, the more time we save, but we definitely lose the fine perception of the space around us, thus we only perceive fragments of reality.

For example, for theorists like Guy Debord, the unity of the city and of space is only the result of the connection of fragmentary memories of these journeys. In other words, for some people, the city can simply be reduced to driving by car from our house, to work and to the shopping center.

Sightseeing Sèvres, a commune in the western suburbs of Paris. Montage made with own photos and a satellite image from Google Maps.

Photography: Ana Marianela Porraz Castillo. 2017. https://www.dropbox.com/s/6dhl7te9lp5yl96/Parcours%20S%C3%A8vres-1.jpg?dl=0

In addition to the above, the confinement that represents the different means of transport in cities (bus, car, tram and subway) have separated us from the overall vision of our environment, as well as the possibility of a direct confrontation with the landscape. If we add new devices such as laptops, tablets and cell phones (in which almost all the passengers are absorbed) the result is a social reality in which we all live alienated in isolated visions.

One thing that architects, urbanists and landscape architects should ask today is how do we intend to give coherence in our territories and cities, if all we see are small fragments of the territory? How do we intend to restore the social fabric of our communities if we have less and less physical contact with other human beings?

4th Street-Herald Square (BMT Broadway Line) station – New York City Subway.

Photography: Aude 2006. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nyc_subway_34st_station.jpg

In fact, it seems to me that one of the keys would be to multiply our way of perceiving and being in the landscape. I believe that nobody denies the advantages of the current systems of transport, but the choice of walking or riding a bicycle gives us the opportunity to change our perspective of the place in which we live.

Likewise, we all benefit from communication systems such as mobile phones, but it is undeniable that human beings also have a strong need for human contact.

High Line Park in New York City July 2011 including the new second section.

Photography:

David Berkowitz, 2011. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:High_Line_Park_the_new_second_section.jpg

So, although it seems that speed and technology prevent us from living the collective experience of the landscape, fortunately there are more and more voices and actions that add to initiatives for the creation of urban spaces for pedestrians and bicycles, thus generating communal meeting places. Day by day more citizens join in the efforts to create new parks and wooded areas.

Being in the landscape is much more than just looking at it from a window or from our computer, is to immerse ourselves in a reality that makes us understand many more things and take an active part in the world around us.

PORRAZ CASTILLO Ana Marianela, Paisajes en construcción: la manufactura de Sèvres y de Jouy-en-Josas (1753-1960), tesis para obtener el grado de maestra en historia cultural y social de la arquitectura y sus territorios, bajo la dirección de Catherine Bruant, Pauline Lemaigre-Gafier, Christel Palant-Frapier, Natalie Simonnot, Annalisa Viati Navone y Jean-Claude Yon. Escuela Nacional Superior de Arquitectura de Versailles (ÉNSAV), junio 2017.

REFERENCES

1 CARERI Francesco, Walkscapes: el andar como práctica estética, Editorial Gustavo Gili, 2002. p. 15

2 Según Careri, estas dos maneras de habitar la tierra se corresponden a dos modos de concebir la propia arquitectura: una entendida como construcción física del espacio y de la forma (sedentaria), contra otra como arquitectura entendida como percepción y construcción simbólica del espacio (nómada). CARERI Francesco, Walkscapes: el andar como práctica estética, op.cit, p. 23.

3 Son elementos megalíticos (piedra grande) con una dimensión vertical importante.

4 Gran cantidad de grupos humanos utilizaron en diversas épocas estos monolitos: egipcios, celtas, mayas, etc.

5 DESPORTES Marc, Paysages en mouvement. Transports et perception de l’espace (XVIIIe-XXe siècles), Paris, Gallimard, collection Bibliothèque des Histoires, 2005.

6 La ciudad futurista era una ciudad atravesada por flujos.