The milpa, life generating cultural landscape

Prior to the “birth of life and the creation of man”, the trees and the vines were created. The presence of vines indicates a healthy and tall monte (low forest), in this natural landscape the man was sent to live, and this space will provide him food and nourishment.

In tropical ecosystems, such as the Yucatan Peninsula, the nutrients are not only in the soil, but they can also be found in the foliage, therefore is not an exaggeration to say that in the jungle, the fertility is on the vegetation.

Starting from this premise, the use of natural resources must adjust to the territory’s characteristics, the Mayas were the ones that found the agricultural system that better adapts to these circumstances: the roza-tumba-quema (cut-drop-burn).

“The system does not destroy the jungle, but preserves it, done under the conditions that favor the system’s fertility, besides; this system is the only viable in Yucatán”. 2

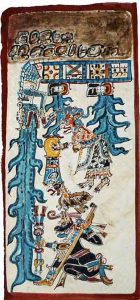

Dresde code (p. 74), representation of

the water and rain ritual with image of god Chaak.

In this system, the production includes beans, pumpkins, pepitas (pumpkin seeds), sweet potatoes, jicama, chili peppers, but mainly corn; all these species compose the cultural landscape that we commonly known as the milpa (cultivation plot).

“Behold here, the beginning of when the making of man was disposed, and when it was searched what must get inside the skin of man… So they found food and that was what entered the skin of the created man, the formed man; this was his blood, from it the blood of man was made. This was how the corn entered [in the shaping of man] by doing of the Progenitors.”

– Popol Vuh 1

Front of Codz Poop building with a reproduction of Chaak god, that is related to the request for water. Kabah, Yucatan.

Fotografía: Aurelio Sánchez, 2013

Why is corn so important?

The corn is the vital matter of the creation of men; it is also the link between the natural and the supernatural, in this natural landscape that becomes sacred and humanized, this is the space that constitutes the monte (low forest).

The monte is not just the place that provides nourishment and raw materials, it is a space that has an owner, so his permission must be requested to enter, cultivate, cut, or live. Then, the purely biological connotation of this space is left behind to embrace a cultural meaning.

“Every place is sacred, every place is owned, but even more the cenotes (sinkholes), the caves, the múules (hills), the ruins, the old roads, the beel moson (roads or course of the swirls), the monte and every place that is alive, has an owner.” 3

Cha’a Cháak Ceremony.

Photography: www.lectormx.com

The ritual that has the major implication to the milpa is the Cha’a Cháak, a prayer to ask for rain, essential for the heavy rainfall crops; the landscape that is recreated in the milpa during the ritual unifies several Maya philosophic concepts, as Mario Ruz 4 explains:

Cha’a Cháak Ceremony.

Photography: www.lectormx.com

A table-altar which represents the communal space (covered with jabin 5 leaves, symbolizing the shrubs) and whose legs are sunken into the ground, stablishing communication with the underworld. Then, starting from the corners, the long branches of xi’imché 6 are suspended, evoking the community firmament.

Around this table-altar, the four cardinal points -Lak’in (East), Chik’in (West), Xaman (North) and Nohol (South)- are risen from the arches that represent the homes of the chaako’ob, lords of the rain; in the center of each of this arches stands a stick-pillar which ends in a cross where the offering pots will be placed. From each arch an xtajkaane’ vine is suspended to join them symbolically to heavens extended over the table.

Trying carefully to direct the thunderbolt, so it will not get lost and other villages receive its humid homage (this is why this vine is called beel-cháak, “the path of the Cháak”). The Maya imago mundi, containing the sky and its wanderings, the earth and its hills, the underworld and its accesses, has been concluded.

Cha’a Ch’áak celebration’s diorama.

Photography: Thomas F. Aleto

All the elements that surround men, within the Maya philosophy, has a cultural connotation; the appropriation of the territory is based upon an universe conception in which all everything has a reason and is interconnected, specially nature. In this manner, the natural resources are used for eating, healing and inhabit.

Through the centuries, these resources have generated a knowledge that is transmitted from generation to generation, and that today is concentrated in the memory and life of the Maestros Milperos (Cultivation Plot Teachers) 7.

The knowledge of the milpa also perpetuates the Maya cosmovision that has interweaved all the catholic religious structure (God, Virgin Mary and The Saints), combined with the forces of “a large series of supernatural entities as Chah, the waterer; Metan Luum, the guardian of the terrestrial animals; or Yum Kaax, guardian of the vegetation and birds, since the arrival of the catholic gods and that before this event, must have been under the power of Itzamna, Ixchel, Ek Chuah or Kukulkan, protector of the ancient powerful social classes.” 2

Cha’a Cháak ceremonial offering pots.

Photography: www.lectormx.com

Talking about the Mexican cultural landscape, the most representative image is the Agavero landscape and the old industrial installations of Tequila, Jalisco, that have been recognized as World Heritage in the category of landscapes that are organically evolved with society, one of the three types that UNESCO stablishes for cultural landscapes (the other two are: clearly defined landscape designed and created intentionally by man and associative cultural landscape).

The milpa also belongs to this category, but if we consider its cultural input and biotic knowledge, it could also be considered in the third category associative cultural landscape; with the distinction that this landscape, unlike the Agavero landscape, is cyclic and it is built each year to nourish Maya families.

La milpa, cyclic landscape that is built each year.

Regardless its great cultural and landscape value, the milpa faces undervalue problems, the lack of information about the benefits that the roza-tumba-quema (cut-drop-burn) system has for promoting the regeneration of the Yucatan Peninsula tropical vegetation, with the proven benefits of a practice that has existed over 2000 years, and has not destroyed the forest, but on the contrary, the extinction of this system produces its disappearance today 2.

Roza-tumba-quema (cut-drop-burn) system.

Photography: Leavingthesafeharbor

REFERENCES

1 Popol Vuh (from k’iche’ words popol: community and vuh: book) is a compendium of legends and stories of the Mayas.

Popol Vuh, Adrián Recinos (traductor), Las antiguas historias del Quiché, (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2012).

2 Silvia Terán y Christian Rasmussen, La milpa de los Mayas (Mexico: UNAM-UNO, 2009).

3 Ella Quintal et al. “U lu’umil maaya wíiniko’ob: la tierra de los mayas”, en Diálogos con el territorio. Simbolizaciones sobre el espacio en las culturas indígenas de México, Alicia M. Barabas (coordinadora), (México: INAH, pp. 273-360, 2003).

4 Mario Humberto Ruz, “Cha’a Cháak. Plegaria por la lluvia en el Mayab contemporáneo”, Arqueología Mexicana, núm. 96 (2009): pp. 35-39.

5 Piscidia piscipula (L.) Sarg.

6 Especie arbórea (Casearia corymbosa). / Tree species (Casearia corymbosa).

7 Aurelio Sánchez Suárez, “Saberes constructivos mayas: cosmogonía tangible” en Coloquio Internacional 20 Años del Documento de Nara. Sus aportaciones en la definición del co