The courtyard: heritage and tradition of domestic open spaces since antiquity

One of the main contributions of cultural landscape consists of valuing humanity’s legacy, beyond monumental works and observing the wealth also present in daily open places. Precincts inherited by different cultures over time, still house multiplicity of inhabitants, functions, and traditions, strengthening historical consciousness at a global scale.

Next, it is proposed to highlight some of the courtyard’s most significant qualities, as a common space in housing units since the first civilizations and in most diverse latitudes, ending with an example of their appropriation, symbol of cultural identity and social union.

Reconstruction of Neolithic housing units, with sky window for stove relief and roof access in Çatalhöyük, Anatolia, dated from VIII-V BC

(Turkey, UNESCO World Heritage since 2012).

Photography: Kathryn Killacky. Consultado en:

http://www.killackeyillustration.com/catalhoyuk

”It is the most perfect integration imaginable of environmental resources” ¹. Reflecting cultural area and group´s worldview, the courtyard seeks to satisfy from functional needs of its inhabitants, through creation of microclimates, regulating lighting, ventilation, acoustics and temperature conditions towards comfort; to the most transcendental ones, providing harmony, hierarchy, dignity², serenity, spirituality and transcendence of human beings projecting its limited nature towards the infinite.

In the first housing complex in Çatalhöyük, Anatolia (millennia VIII-VII BC), interior space connected with sky windows to vent the smoke from the central stove, as a possible functional explanation to the origin of the private courtyard³, and a staircase allowed access from the rooftops.

This design evolved to Sumerian dwelling in Mesopotamia (III century BC), with rooms arranged around a central courtyard, surrounded by a balcony organizing family rooms on a second level4, brick flooring and drainage in the courtyard’s center⁵.

Circular courtyards in tulou, traditional multifamiliar housing units built between XV and XX centuries in Fujian, China (UNESCO World Heritage since 2008).

Photography: Song Xiang Lin

They are found in such diverse forms, from orthogonality and introversion, in courtyards of Mesopotamian and Greco-Roman dwellings (as a relief from urban pressure in constantly growing settlements), to the fluidity of circular courtyards or confined by a series of housing units in native cultures in Africa, America, East and Oceania.

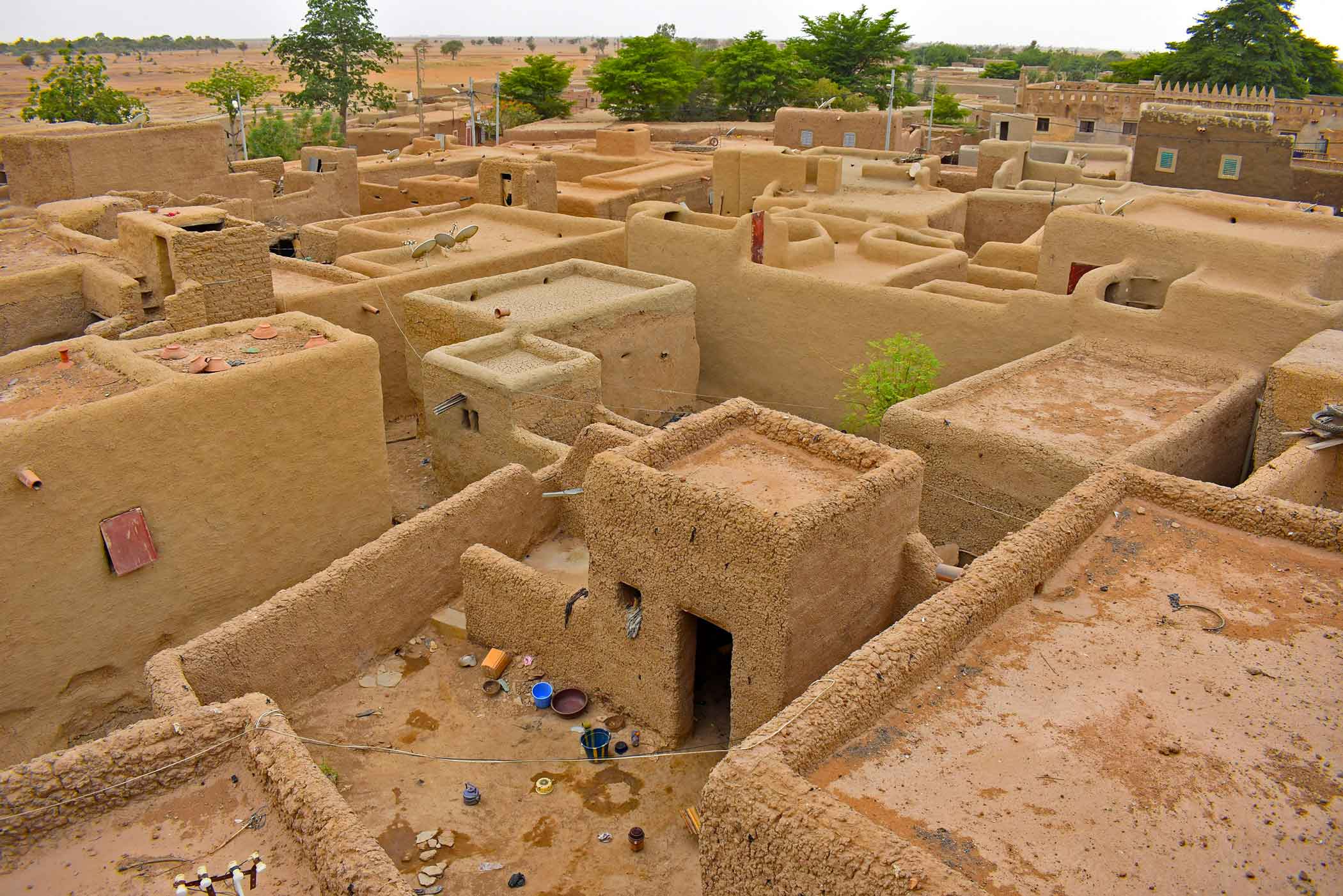

Sequence of courtyards in housing units, excepcional examples of earth architecture in Djenne, Mali (since III BC, UNESCO World Heritage since 1988).

Photography: UNESCO.

In this last ones, it prevails a more organic, extroverted and permanent dialogue with nature, offering growing versatility of independent family units, in contrast to Western prototypes.

They are manifested in a set of horizontal and vertical elements, with a broad spectrum of natural and synthetic surfaces, in dialogue with water bodies; furniture, sculptural objects and worship images, framed by the plant palette in ground covers, shrubs, and trees at varying heights, including fruit and flower trees. These rich compositions of light and shadow, colors, textures, aromas, sounds and even flavors, have raised quality of daily life over time.

An exceptional example is the “Fiesta de Los Patios” in Córdoba, an iconic Mudejar site in southern Spain. People in the traditional neighborhoods worked fervently in the ornamentation of planters, trellises, and communal patio balconies throughout the year. Since 1918 and revitalized in the 1950s, they hold meetings, competitions, and popular shows, over twelve days at the beginning of each May.

La “Fiesta de los Patios”

Photography: ÁLEX GALLEGOS

“In all cases, hierarchy, composition, and privacy are due both to social patterns, transition to inmediate spaces and linkage to outside world.”

In these unique paradises, social integration, interculturality, solidarity, knowledge sharing between generations and respect for natural environment are encouraged. For these and more reasons, on December 6, 2012, it was added to UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list.

These corners continue to excite resident’s senses from the beginning, transcending boundaries and remaining in collective imagination and emotional memory, as celebrated by “Patio” by Jorge Luis Borges in:

“At evening

they grow weary, the patio’s two or three colors.

Tonight, the moon, bright circle,

fails to dominate space.

Patio, channel of sky.

The patio is the slope

down which sky flows into the house.

Serene,

eternity waits at the crossroad of stars.

It’s pleasant to live in the friendly dark

of an entrance, a vine and a well”⁷.

La “Fiesta de los Patios”

Photography: ÁLEX GALLEGOS

REFERENCES

1Rafael Serra, Arquitectura y climas (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1999), 62.

2Vicente Guzmán Ríos, Espacios exteriores. Plumaje de la arquitectura (México: UAM Xochimilco, 2007), 237-248.

3Richard Weston, 100 ideas que cambiaron la arquitectura (Editorial Blume, 2011), 34.

4Adriano Cornoldi, La arquitectura de la vivienda unifamiliar. Manual del espacio doméstico (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1999), 66-68.

5Sigfried Giedion, El presente eterno: los comienzos de la arquitectura (Madrid: Alianza Forma, 1988), 199.

6 UNESCO, “La fiesta de los patios de Córdoba,” UNESCO, https://ich.unesco.org/es/RL/la-fiesta-de-los-patios-de- cordoba-00846. y Córdoba24, “La fiesta de los Patios 2019,” Cordoba24, https://www.cordoba24.info/html/patios.html.

7Jorge Luis Borges, “Fervor de Buenos Aires” Edición 1969. Literatura.us, https://www.literatura.us/borges/fervor.html.