Landscape History of the Chicxulub Crater

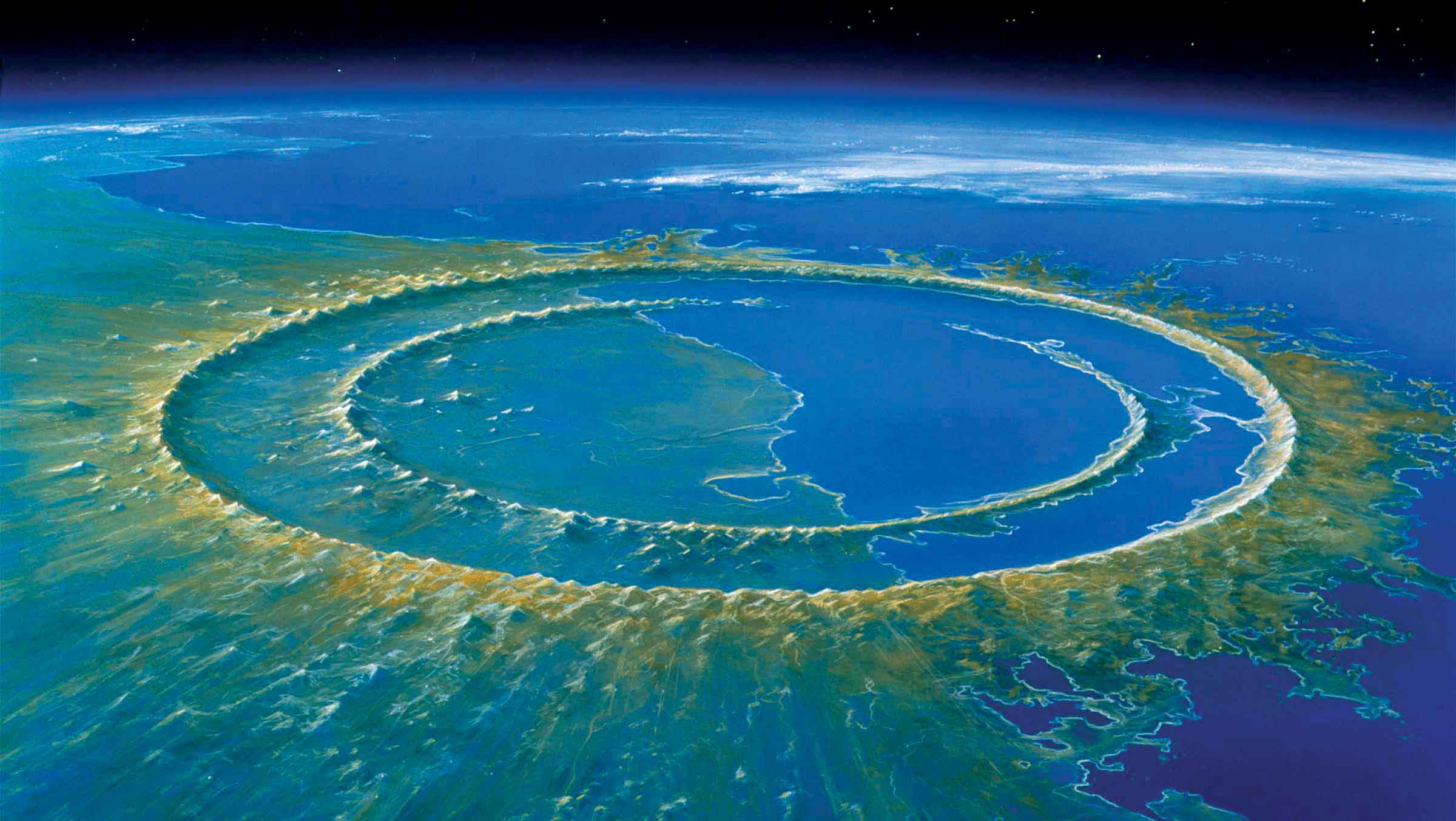

Ah Nakuk Pech, chronicler and lord of Chac Xulub Chen (nowadays Chicxulub), saw the arrival of the Spaniards in 1511 1. He never imagined that his territory would have been the epicenter of another disastrous impact, when 65.5 million years ago, a meteorite of 180 km in diameter collided Earth.

I am Nakuk Pech, descendant of the ancient noble conquerors of this land, in the region of Maxtunil. I was put to save it for my lord Ah Nahum Pech. And in good will I do here the chronic and history of Chac Kulub Chen. (Ah Nakuk Pech)

So far, scientists have found on our planet about 150 geological structures as the result of the impact of meteorites 2.

When a body of this nature impacts Earth’s surface, a large amount of energy is released as heat, which vaporizes the water and the rock of the surface, generating carbon dioxide (CO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2) and a great amount of dust.

In the case of the Chicxulub meteorite, changes in the atmosphere were so extreme that caused the massive extinction of the species that once inhabited Earth.

The biological consequences of this impact have been discovered in recent decades, thanks to various scientific studies and to the satellite technology 3.

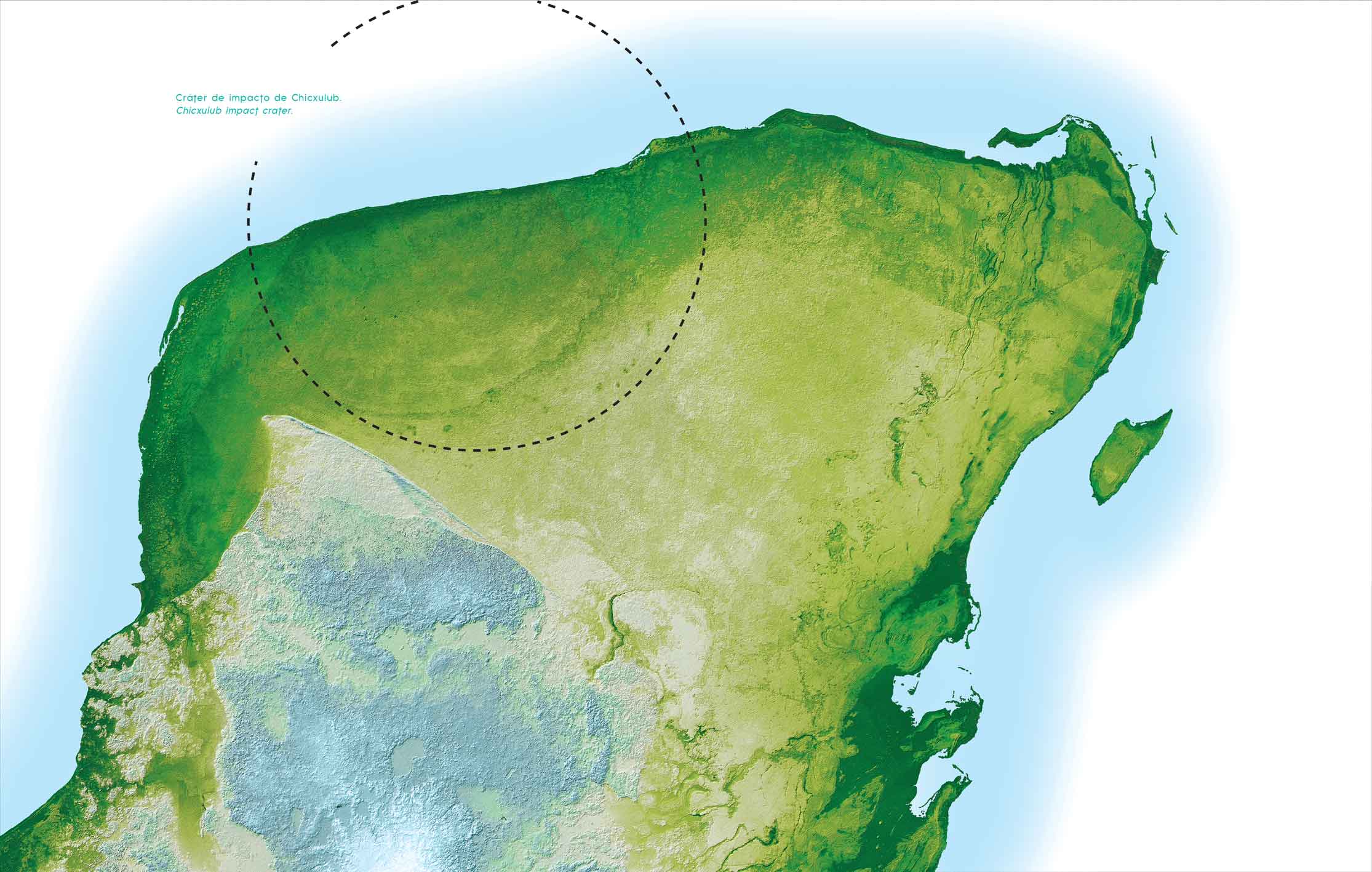

One of the most significant findings was the discovery of the ring of “cenotes” 4 or sinkholes in the Yucatan Peninsula. It is considered that the highest concentration of cenotes in this alignment was originated by the impact, which caused that the rock presented a tendency to dissolve.

According to Dr. Eduardo Batllori 5, the northwestern part of the peninsula has been called “The Sedimentary Watershed of Chicxulub.”

Such region or hydrogeological watershed, bounded by the aforementioned ring of cenotes, is characterized by a sedimentary limestone platform with a generally even surface and the presence of an underground coastal aquifer waters that flow into the Gulf of Mexico.

It is worth mentioning that the ring of cenotes tends to isolate, in hydrological terms, the Chicxulub watershed from the rest of the Yucatan Peninsula, this represents a high fragility in terms of the aquifer contamination.

Photography: NASA,JPL.

The Yucatan peninsula emerged from the sea 13 million years ago.

On this region of low tropical forest, warm weather and shallow soils, was where the Mayas of the peninsula built their cities towards the post-classic.

The four cardinal directions (Sak, Ek‘Chak, K’an), the world’s axis (Yaax), the underworld (Xib’alb’a), the overworld (K’aan) as well as the equinoxes and solstices, shaped the spatiotemporal references from which the Mayans planned their settlements.

Similarly, in the Mayan worldview, the cenotes were considered sacred places since they constituted the entrance to the underworld.

Cenote Ik Kil, Yucatán, México.

Photography: Boris G

According Ah Nakuk Pech, it was the fifth division of Katún 11 Ahau 6, when the Spaniards settled in the great city of Thó. From the impact of these two cultures also emerged the current population of Chicxulub, located at the epicenter of a large watershed, certainly unique in the world.

This underground landscape, composed by skinholes, caverns, and underground rivers, is essential to the coastal landscape, especially because from the encounter of this sweet water with sea water are formed generous lagoons, placed some kilometers away from the beach, where proliferates several species of mangrove and grasslands.

The importance of this water from the aquifer is fundamental for the ecosystem, however in the last decades it has become alarmingly polluted, putting at risk, not only the natural environment, but the sustainability of the coastal villages.

Therefore, new strategies need to be reconsidered in the construction and wastewater treatment fields, over the whole basin crater, but especially in coastal areas and in the sinkholes ring area, both with higher permeability into the subsoil.

Reference:

1 Nakuk Pech, Historia y crónica de Chac-Xulub-Chen (México: Departamento de Bibliotecas de la Secretaria de Educación pública, 1936).

2 Bevan M. French, Traces of Catastrophe: A Handbook of Shock-Metamorphic Effects in Terrestrial Meteorite Impact Structures (Houston: Lunar and Planetary Institute, 1998).

3 Martin Connors, Alan R. Hildebrand, Mark Pilkington, Carlos Ortiz-Aleman, Rene E Chavez, Jaime Urrutia-Fucugauchi, Eduardo Graniel-Castro, Alfredo Camara-Zi, Juan Vasquez, y John F Halpenny, “Yucatan karst features and the size of Chicxulub crater,” Geophysical Journal International, Num. 127 Vol. 3 (1996): F11‑F14.

4 Cenote, from the Mayan word Dzonot, the scientific term is sinkhole. Underground cavities product of the weathering or dissolution of the stone, phenomenon also known as “karst”.

5 Eduardo Batllori-Sampedro, Julio Iván González-Piedra, Julio Díaz Sosa y José Luis Febles-Patrón, “Caracterización hidrológica de la región costera noroccidental del estado de Yucatán, México,” Investigaciones Geográficas. Boletín del Instituto de Geografía, UNAM, Núm. 59(2006): 74-92.

6 Date of the mayan calendar, estimated to correspond to year 1542 A.D.