The development and current role of Landscape Architecture

Since the Shanghai World Expo in 2010 and the implementation of the Agenda 2030 on the Sustainable Development Objectives, UNESCO adopted within its priority strategies, “to achieve that cities and human settlements are inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.”

Not only limiting itself to the provision of quality equipment, but stating that “the actors responsible for urban policy should include issues such as migration, integration and cultural diversity, environmental management and protection of natural resources” 2.

Similarly, from the conception of landscape as a “system integrated by complex and diverse components formed under natural and anthropological processes, in constant interaction and development” 3, the determination of the discipline of Landscape Architecture emerges as an analysis and design tool focused on the dialectic between man and the environment in various scenarios.

“There is no landscape culture without careful treatment of the territory” (Francisco de Gracia, 2009)

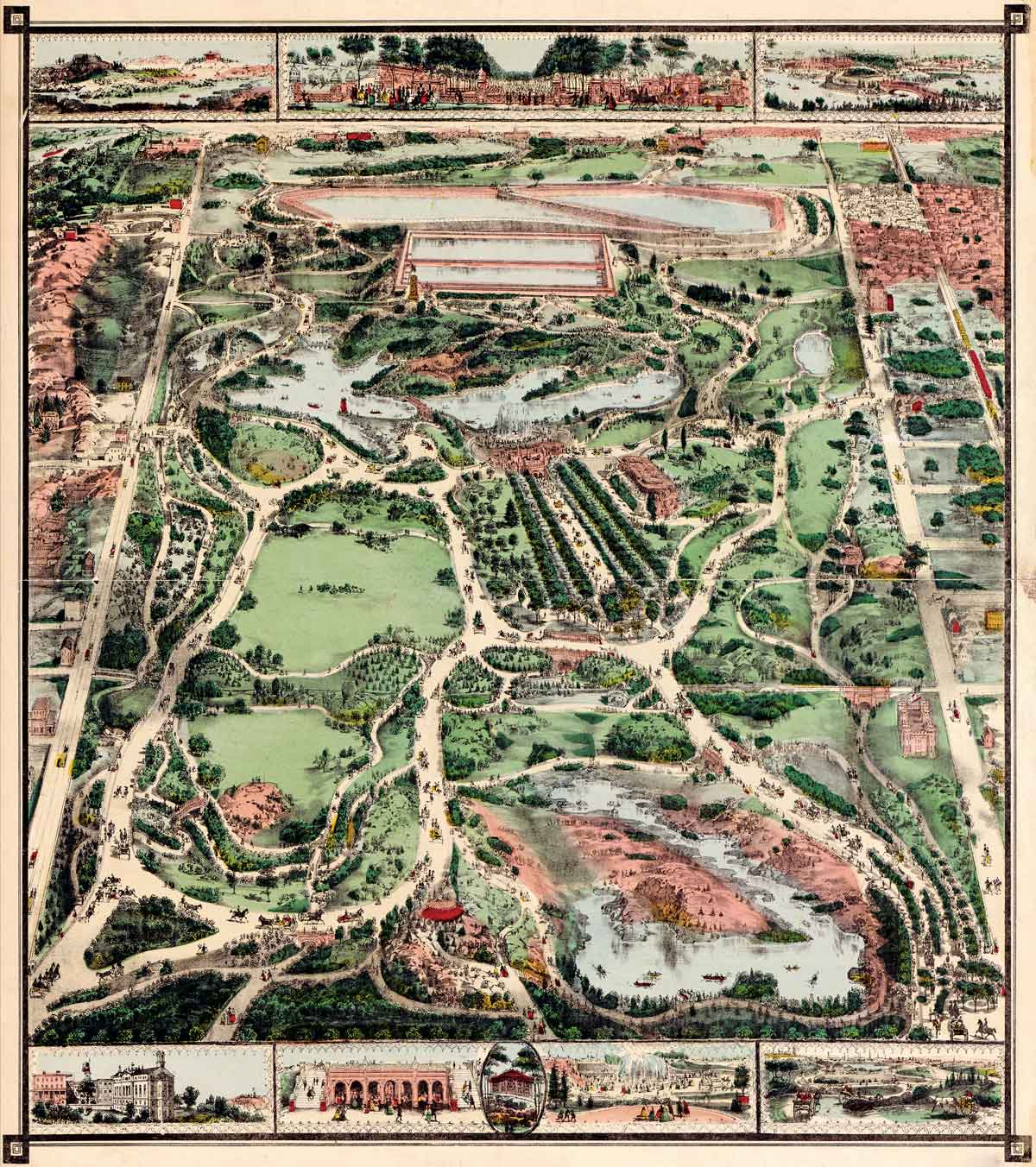

A detailed and interesting map of the Olmsted’s Central Park in New York City, at its beginning, depicted here around 1860.

“Landscape Architecture…an analysis and design tool focused on the dialectic between man and the environment in various scenarios.”

From both contemporary perspectives on human settlements, as well as taking into account the role of many actors and the potential of intervention on the territory, it is essential to look into the History of Landscape, since it “allows us to know how human communities have seen and interpreted the immediate space, how they have transformed it and how they have established ties with it” 4.

In retrospect, human intervention on the territory has mainly reflected economic, aesthetic and ecological-environmental reasons. This process of anthropization has gone by since the predominant physiocratic 5 trends from the 18th century, towards the productivism of the 19th century 6.

The circumstances of contemporary urban settlements are the result of this intensive exploitation of natural resources and human capital, which accompanied by aggressive urbanization processes, has generated that the citizen is found more and more detached from the environmental condition.

Throughout the history of mankind, different cultures have contributed to the composition of landscape three primary currents are identified. The rational-objective trend, where the geomorphology of the territory prevails over architecture, exemplified in traditional buildings.

Ecological Corridor and Recreative of the Eastern Hills in Bogotá, Colombia. Diana Wiesners.

Second, formal-geometric trend distinguishes itself towards the intellectualization and reordering of the environment, exemplified in the gardens of Andrea Palladio’s Renaissance and André Le Notre’s Baroque.

In contrast to this currant, the organic-picturesque movement is characterized by domesticated naturalism, reflected in the garden of Stourhead (illustrated at the end of the article) of Henry Flitcroft (1697-1769), British landscape icon 7.

“Landscape Architecture contributes to the re-significance of the place, exploring new proposals on open spaces for the sake of sustainability.”

On the professional practice of Landscape Architecture, American Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) is recognized as a pioneer of the discipline, developing around 550 projects of parks, residential communities and college campuses, highlighting Central Park in New York, the Emerald Necklace in Boston and the Niagara Falls reserve, all of them reflect his concern to “preserve areas of natural beauty for the public enjoyment” 8.

Inca aqueduct in Tipon, Cusco; a prehispanic design strategy on sustainable water networks in harmony with the environment.

This legacy remains in force through the magnificent examples of sustainable and resilient practices (for example the Inca aqueduct illustrated on the next page) in contraposition to schemes of exacerbated consumerism that characterizes contemporary western societies.

Through the appreciation of the immeasurable legacy represented by traditional life patterns, and taking in account the current urban and environmental issues, landscape architecture contributes to the re-significance of the place, exploring new proposals on open spaces for the sake of sustainability.

Expressions such as Land Art, the integration of urban gardens to neighborhood’s equipment, the innovative models of planning and management of green infrastructure, the provision of new collective environments, mobility and environmental quality in cities (as illustrates the project of Diana Wiesners on the next page), are just a few examples of the contributions of Landscape Architecture in contemporary environments.

Stourhead National Trust Gardens in Wiltshire. Stourhead is a 1,072-hectare estate at the source of the River Stour near Mere, in the county of Wiltshire, England.

Confronting these challenges and opportunities, Landscape Architecture combines multiple viewpoints: from scientific knowledge, social areas and design, to traditional practices; providing innovative solutions to increasingly hostile environments.

This awareness effort begins with the observation and a deep analysis of the territory, identifying the actors and the impacts as part of the historical processes and integrates this diagnosis to the planning and management of land use.

The interdisciplinary vision of the landscape architect allows him to enlarge his perspective as a global citizen and lets him intervene as an agent of change on the dynamic of human settlements.

In the same manner the professional designs on diverse gradients: from protected areas, through the rural scene, to the urban and architectural level; ascribes value on the environmental, sociocultural and patrimonial capital and creates a sustainable scenario for present and future generations.

REFERENCES:

1 UNESCO, “Agenda 2030: Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible,” (2015), consultado el 9 de abril de 2016. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/cities/.

2 UNESCO “Building Sustainable, Inclusive and Creative Cities,” (Expo Shangai, 2010), consultado el 9 de abril de 2016. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/shanghai-world-expo-2010

3 Isabel Rigol Savio, Programa de Desarrollo de Capacidades para el Caribe. Módulo 4. Gestión de Paisajes Culturales (La Habana: UNESCO, 2004), 10.

4 Pedro S. Urquijo Torres y Narciso Barrera Bassols, “Historia y paisaje. Explorando un concepto geográfico monista”. Andamios. Revista de Investigación Social 5-10 (2009), 227-252, consultado el 9 de abril, 2016, http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=62811391009ç

5 Tendencia fisiócrata: Concepción de la naturaleza como fuente de riqueza y la actividad agrícola como causa de bienestar social. Obtenido de De Gracia, Francisco. Entre el paisaje y la arquitectura. Apuntes sobre la razón constructiva. San Sebastián: Nerea, 2009. 21-26.

6 Productivismo: Donde el medio natural era el principal soporte de la actividad económica e inician los procesos de desintegración entre campo-ciudad, hasta el consolidado mercantilismo que impera hoy en día. Obtenido de De Gracia. p. 21-26.

7 Obtenido de De Gracia, Francisco. p. 36-41.

8 “The acomplishments of Frederick Law Olmsted”, consultado el 12 de abril, 2016, http://www.fredericklawolmsted.com/work.html