To the Edge. (Wild) Landscape of the Urban Periphery

In the article “Pull Over to the Edge. (Wild) Landscape of the Urban Periphery”, by Pamela López, the author reflects on the city’s edges as territories of vertigo, where the wild and the civilized intertwine, revealing the boundaries, frontiers, and forgotten landscapes that still persist in the periphery.

Standing at the edge of something brings vertigo. On a social level, it also feels like a leap of faith into the unknown —into the invisible truths of everyday life shared by many people, plant communities, animal groups, climates, and their interactions— all of which we call landscape. Are our landscapes feeling vertigo too? There are more and more edges, limits, borders. Local news reports new lines that “divide” territories, whether due to geopolitical reasons or physical changes such as subsidence or flooding.

Are our landscapes feeling vertigo too? There are more and more edges, limits, borders.

Edges are created —sometimes intentionally, sometimes as a consequence—, which contrasts with what Alexander von Humboldt taught us in the 19th century. Through his diagrams of strata, his writings on “climatic changes,” and his tireless texts and drawings, he urged us to see the invisible, to recognize the gradients behind transformation, and to establish connections, not boundaries.

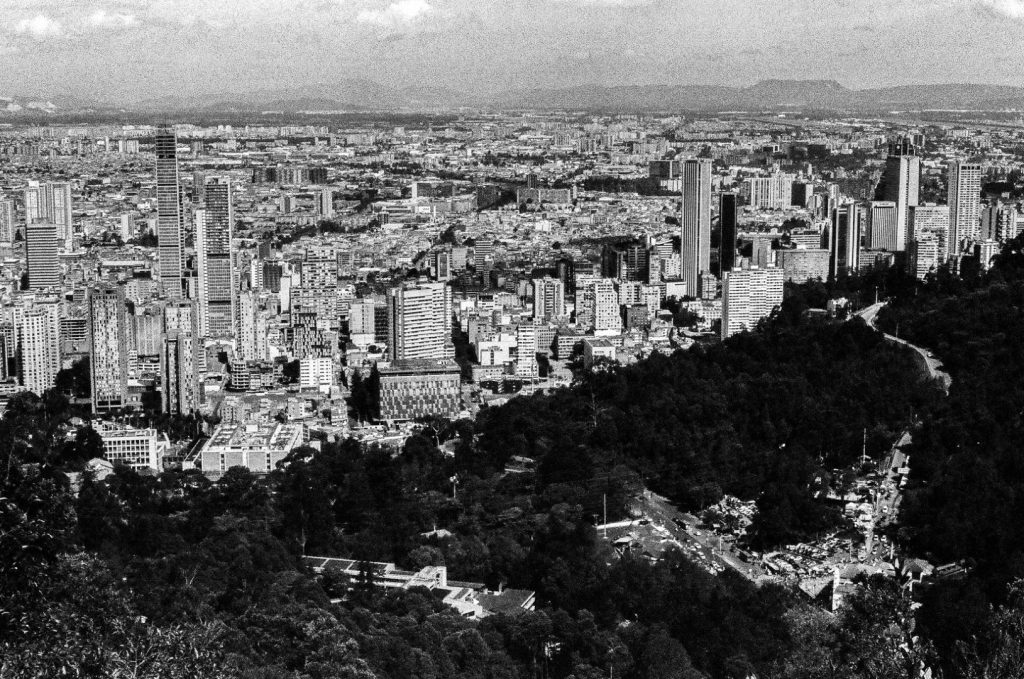

Bogotá desde el cerro / Bogotá from the hill

Fotografía / Photography: Geraldine Montenegro Valero

Nothing is fleeting, least of all boundaries. Historically, the edges of cities were defensive walls or transitional zones between the “wild” and the “civilized.” I propose to see it in reverse: in contemporary grounds, the wild may be the relentless urban sprawl, while the civilized is merely a relic of the past.

To be wild has been a symbol of otherness, of voracity, of strangeness —of what refuses to obey rules. Even plants that grow spontaneously in urban contexts are labeled “wild vegetation” and must be removed, because they don’t fit the manicured garden.

The word “wild,” from the Latin silvaticus (from silva = forest), reminds us that once “to be wild” simply meant being part of the ecosystem. In today’s context of urban expansion, to be wild means to remain part of a complex natural system, not as something alien or untamed.

La calma y la tormenta / The calm and the storm

Fotografía / Photography: Camilo Fabian Rojas Zapata

From this premise, being wild requires us to acknowledge what we are doing to create gradients and promote ecological patches within this ever-expanding cloud of concrete. Some sectors cannot absorb it all, yet the wild landscape leaves behind relics of the ecosystems that once were reservoirs of biodiversity.

We call those relics vacant lots, fields, wastelands. We treat them as otherness, turning them into dumps or “no man’s lands,” forgetting to recognize what they once were before we “civilized” them.

Naturaleza urbana / Urban nature

Fotografía / Photography: Ryller Chrystian de Andrade Veríssimo

A clear example is the hydrological system of canals and waterways in Xochimilco, Tláhuac, and Iztapalapa —the so-called “Conurbated Zone”—, which is nothing more than two urban centers merging into one.

Those who view Mexico City from afar read its urban landscape without nostalgia or hierarchy: without romanticizing the center or excluding the east, without elevating the west or overlooking the south. The Megalopolis is a daily act —thousands of people cross hills, lakes, and volcanoes, spending hours of their lives on that journey. As Gustavo Cerati wrote: “In weaving attempts, rage weighs more than cement.”

In this wave of change, designing with the city requires biocultural strategies to restore its lacustrine vocation. In the rainy season, it means allowing the water to return; in the dry season, it will be another story. As a landscape architect, I applaud it; as a citizen, I demand it; as a Latin American woman, I celebrate it.

Fronteras urbanas: Los márgenes habitados de Cali, Colombia / Urban Frontiers: The Inhabited Margins of Cali, Colombia

Fotografía / Photography: Andrea Carolina Cortes Ochoa

We can begin erasing boundaries, stop pushing everything to the edges. If a catastrophe arises there, it may not be visible at first, but its effects can be read in water, fire, food, and migrations —human and non-human. As they used to say in Mexico City’s old traffic slang: “Pull over to the edge.” Today I suggest we truly do so —to weave at the borders and keep the system’s fabric from unraveling.

Landscape is expression. I wonder if, within its spatiality, also lies the resistance to falling off the edge —to the periphery of a city.