The landscape and the departed

Surely, to anyone who is not a Mexican, it will seem lugubrious or ghoulish to celebrate the dead: to prepare them food, invite them to your house, gather with them and evoke their presence for several days each year.

However, in our culture death is celebrated as a tradition full of folklore, color and rituals that have been practiced for hundreds of years, being the Day of the Dead one of the most important celebrations of the country.

Photography: Ariel Da Silva

In late October and early November, this landscape full of absences has both physical and emotional impact on our environment. The houses, streets, markets, cemeteries and mausoleums are temporarily transformed into altars, procession routes and places of conviviality.

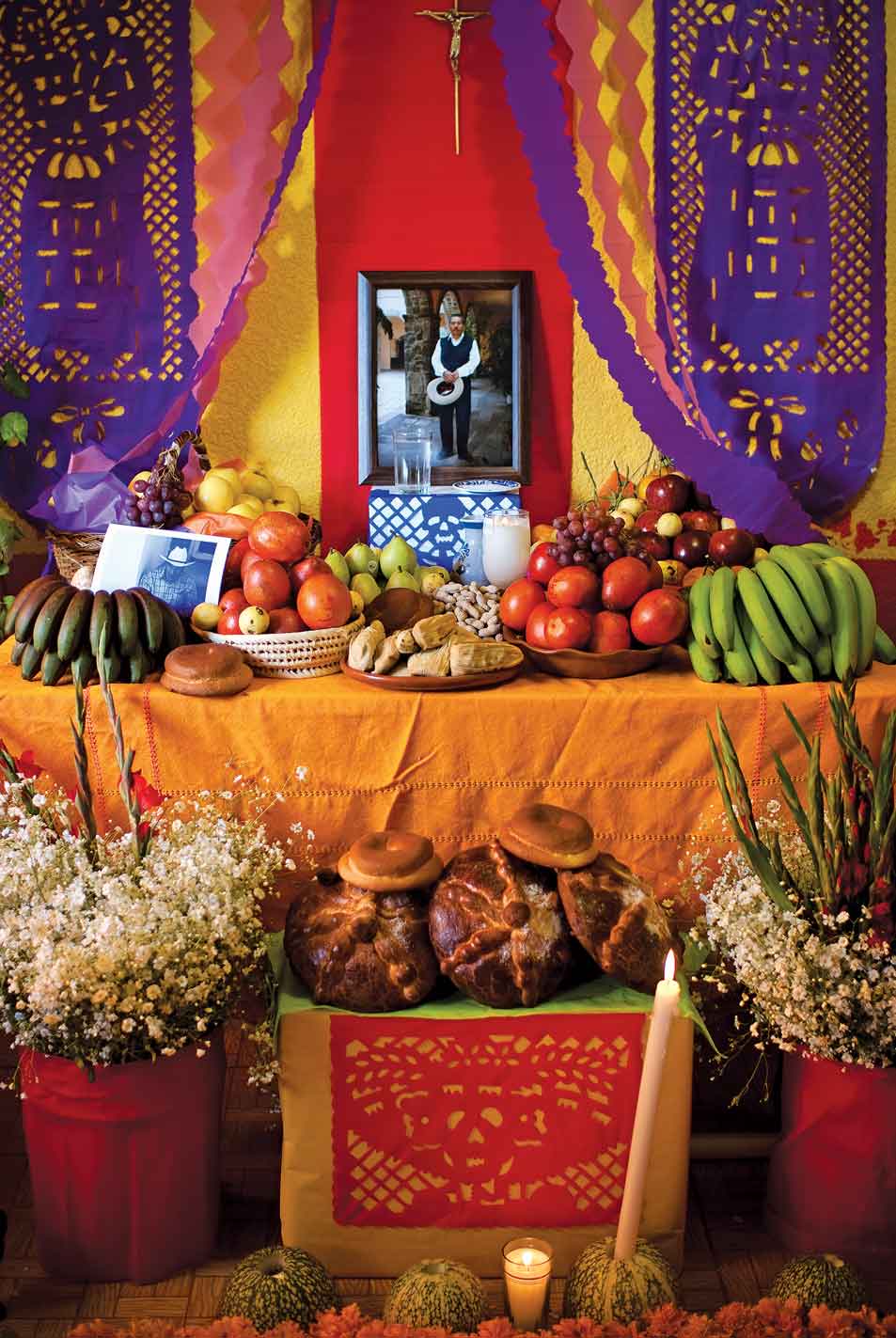

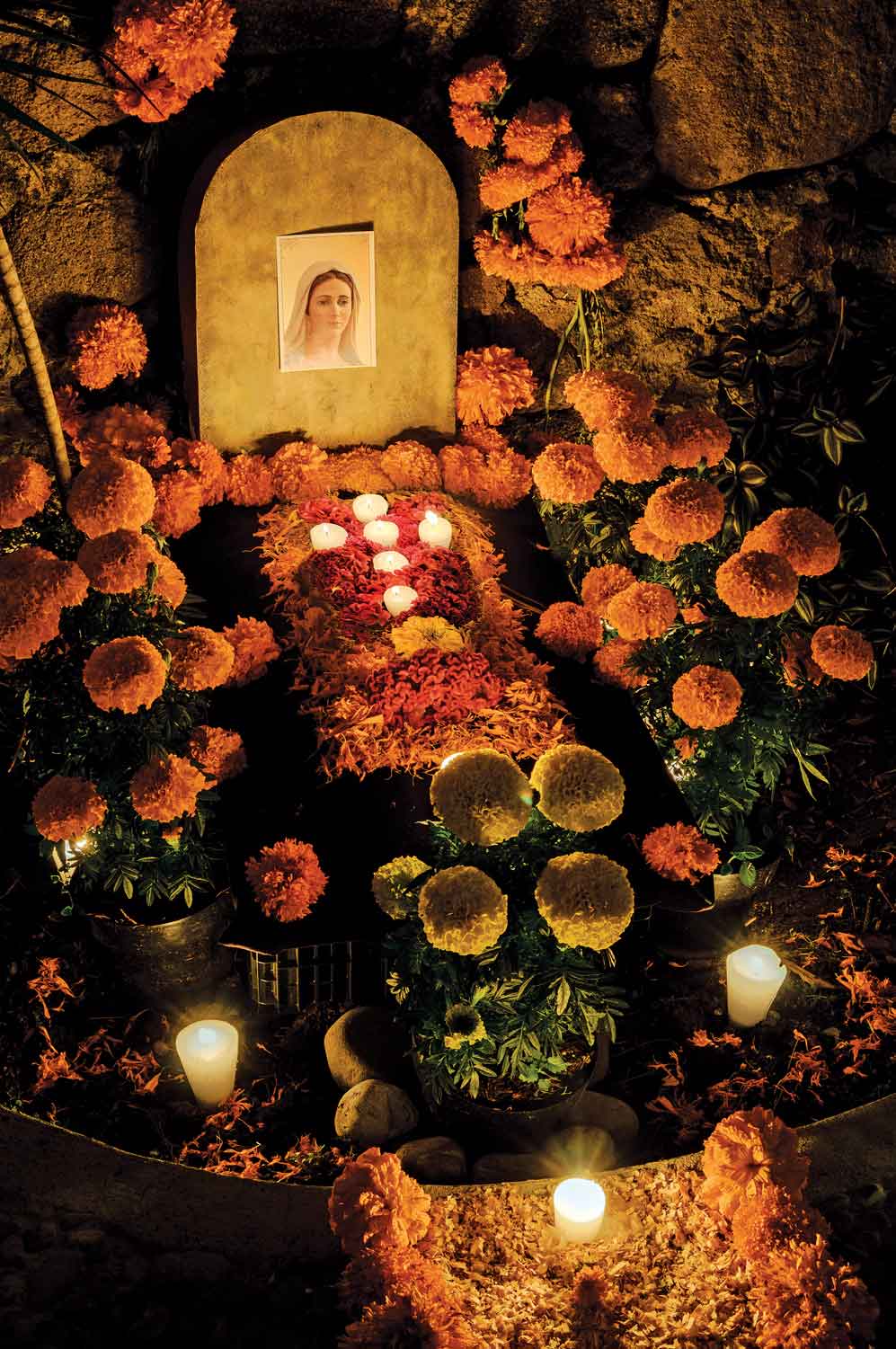

Dressed for a party and painted in the orange of cempasúchil flower, urban and natural landscapes (depending on the area of the country), are converted by the construction of altars of all kinds: ephemeral architecture that pays homage to the departed.

Photography: Eneas de Troya – http://www.flickr.com/photos/eneas/4072192627/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11952725 y By Paolaricaurte – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44667651

The altars of the dead, full of memories and color, transform the landscape temporarily.

Photography: Eneas de Troya

Photos, food, sugar skulls, dearest objects and other items that the dead used to liked when they still belonged to this world, suddenly appear and transform a landscape usually static, sad and solemn, into one full of color and loaded with mysticism.

The end of the summer, accompanied by its particular climate change, announces the closeness of this epoch which is perceived as magical.

That is when the preparations to receive and honor the souls of the dead begin. The house, the furniture, the yard, the streets and the tombs of the cemetery are cleaned. The typical food of each region is prepared for this holiday, and also the food that the deceased relatives and friends used to like the most.

The altar is installed to await the arrival of souls. The light, smells and colors of these elements guide them to the place. Photography: Juan Euan Photography

Photography: Jordi Cueto-Felgueroso Arocha – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36686950

The design and composition of the altars respectsthe complexity of traditional elements and turns them into true works of art.

The landscape transforms: the absence and the memory of the departed prevails for the celebrations of each year.

Photography: Jordi Cueto-Felgueroso Arocha – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36686950

Photography: Juan Euan Photography

The pre-Hispanic custom of celebrating the dead has its variants and its own characteristics in each region of the country.

In Yucatan, for example, the strong tradition of “Hanal Pixán” or “The Feast of the Souls” is preserved since the precolonial time, in which Mexican Day of the Dead customs that are practiced in almost all of the Republic intertwine with other more local traditions, still practiced by indigenous Mayan communities in the region.

October 31 is the day of children and their altar is adorned with colorful candles, fruits, toys and treats.

The next day, November first, the altar is dedicated to dead adults. Colorful candles are replaced by black or white candles and some belongings that were part of their tastes or habits are added.

Photography: Juan Euan Photography

On November 2nd families visit the cemetery to accompany their deceased relatives. The family members stay all day at the site, people pray for the departed and eat.

On November 3rd, amid prayers and songs the souls of the dead leave the world of the living. Candles are lit next to the doors and windows to guide them in their return to the beyond.

The food is placed on the altar, the family gathers around to pray. The next day, the plates are removed from the altar and consumed by the family. Photography: Juan Euan Photography

This beautiful Day of the Dead tradition, which is practiced in all parts of the Mexican Republic, demonstrates the adaptability of landscapes.

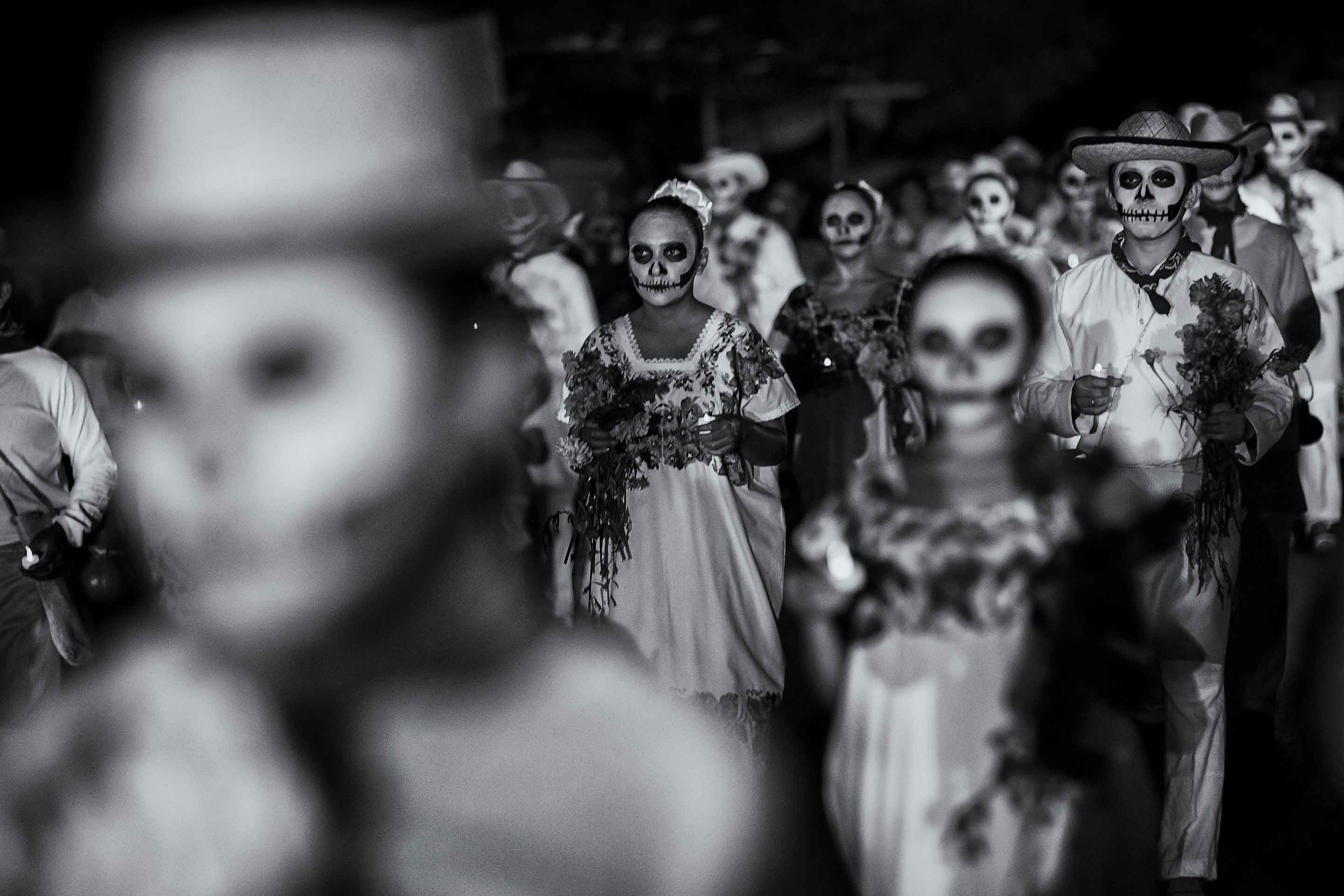

Temporarily rivers, lakes, coasts and streets become places of procession filled with color during the day and glow with the fire of candles at night. Outlines change and take the form of crosses, flowers and skulls. Their sounds are converted into songs and prayers.

“Walk of the Souls” in Merida, Yucatan. Photography: Juan Euan Photography

Gravestones turn into tables, streets into carpets of sawdust and flowers.

The edification of altars in public and private spaces transformed context morphology with fleeting colors and shapes that remind absences, and that are able to bring back the loved ones who have left us.

Subsequently the common landscape, which is always imposed back, returns to its original state having witnessing that the dead neither die nor leave, but are added every year, in the form of invisible presences, to that everyday landscape.