The mayan house

These households are a part of the maya cosmogonic landscape, as this type of housing is also the home of their gods, located in the sky and the underworld.

By: Aurelio Sánchez

The natural landscape has always been the admiration of human beings; shaped by nature through the centuries, this landscape has motivated its humanization in different ways: sometimes being transformed for exploitation purposes and in other occasions receiving different meanings of the way each culture conceives life and the creation of the universe.

In the Maya region the natural landscape was one of the sources of inspiration that were used to build the cosmogony described in documents, mural paintings or epigraphs.

One of the most important documents is the Popol Vuh, which narrates the creation of the universe: “…great was the description and the story of how heaven and earth were formed, how the sky was pointed out and measured and how the measuring cord was brought and it was extended in heaven and on earth, in the four angles, in the four corners 1…”

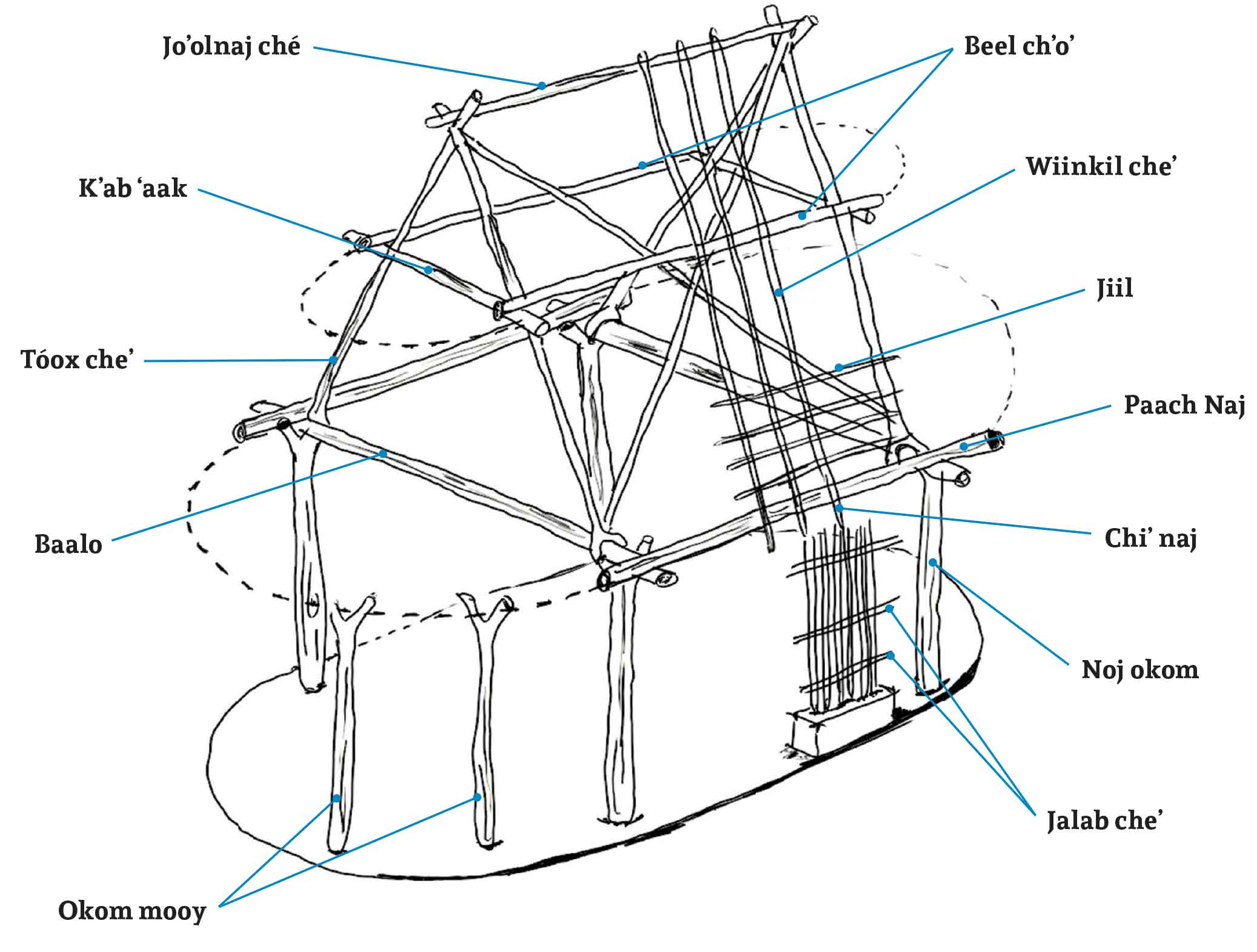

The story of the Mayan housing builders resembles the Popol Vuh in the layout and planting of its four noj okom (main pillars), process that has been reproduced through millennia without substantial changes.

These households are also part of their cosmogonic landscape,as this type of housing, built with wood, reeds, palm, grassand soil, is also the home of their gods, located in the sky andthe underworld.

Representation of the Mayan house. Northern building of the Nunnery Quadrangle in Uxmal.

Photography: Aurelio Sánchez, 2009

Author’s collection

The cities of the Mesoamerican period have been commonly defined by their large ceremonial centers that show its monumental architecture, notwithstanding that the largest extension of its territory were homes, in a settlement pattern that allowed the existence of crops of different plant species, creating a landscape that today would be called a “garden city” 3.

With the arrival of the Spaniards this landscape was altered by imposing a new morphological order, with a Renaissance settlement pattern that imposed a reticular layout of Greco-Roman influence. Many of the novohispanic settlements were of Mesoamerican origin in its creation, preserving the morphology of open spaces, public wells and sacbeo’ob (“white roads”).

Image: Aurelio Sánchez

Illustration: Bettina Vargas

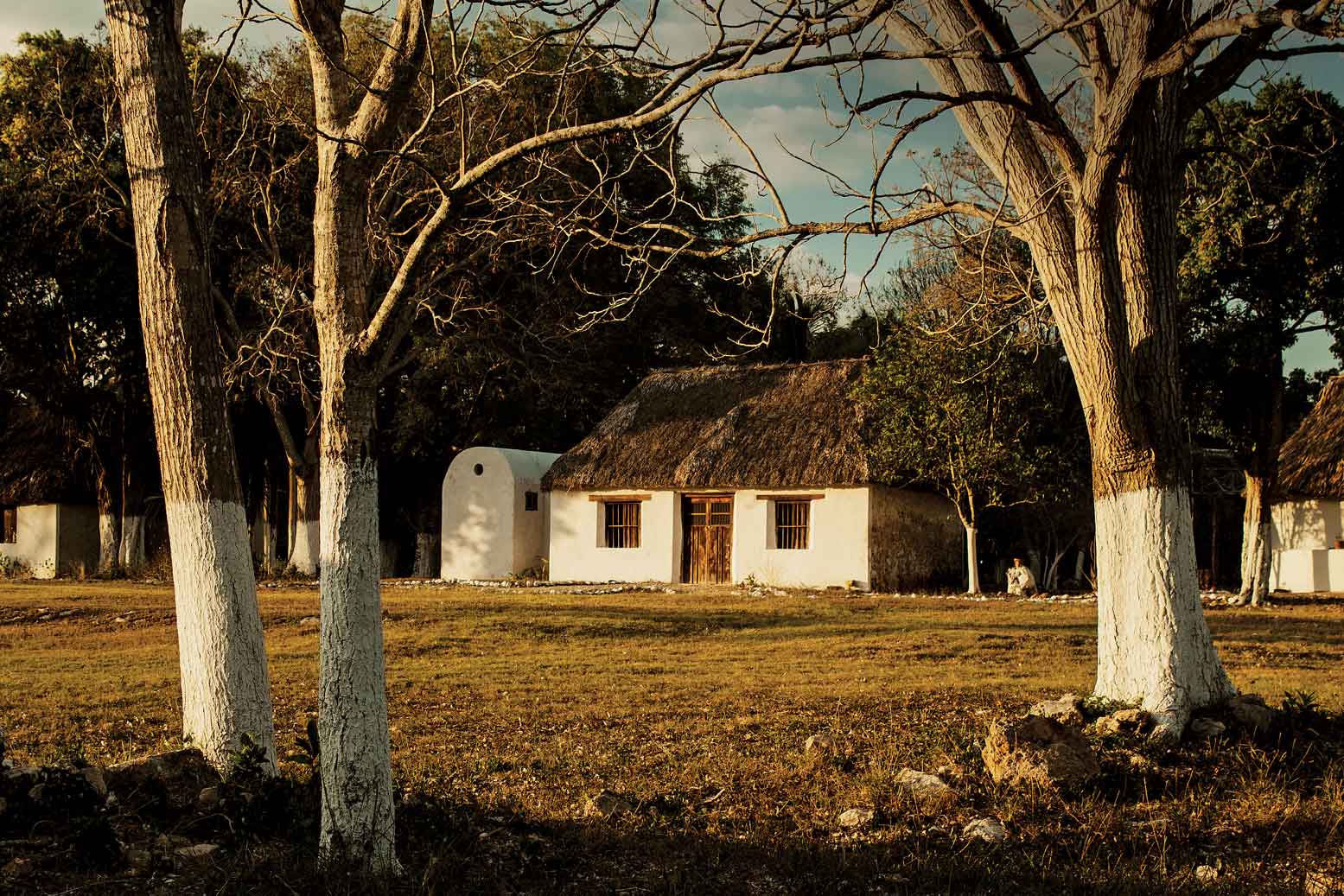

The resilience of the symbolic elements, that belong to the Mayan people’s identity, has defined the cultural landscape of villages in the states of Yucatan, Campeche and Quintana Roo.

While members of the commonly called Mayan culture live both in cities as in the rural area, when speaking of its landscape we always evoke images that for centuries have been part of its identity and worldview: the house of wood, palm and “bajareque” 4 or masonry, framed by the stonewalls that delimitate the parcel that continues to shape a garden settlement, with both endemic and imported plants, with the existence of wells within the solar or public on the streets or open spaces.

The representation of the body and celestial elements are present in the Mayan house which comes alive with the spirit of its inhabitants.

CONSTRUCTION ELEMENTS OF THE MAYAN HOUSE

- Noj okom (noj: big thing and okom: wooden pillar, “big wooden pillar”). Four pillars that function as a support for the cover structure.

- Baalo Main crossbars that rest on the noj okom.

- Paach Naj (pach: back and naj: house, “back of the house”). Crossbars that define the main frame of the house and the height of the walls.

- Tóox che’ (tóox: that supports and che’: wood, tree). Structure that stiffens the cover.

- Jo’olnaj ché (jo’ol: head, naj: house and che’: wood, tree, “head of the wooden house”). Superior joist of the house.

- K’ab ‘aak (k’ab: arm and áak: turtle, “arm of turtle”). Secondary crossbars.

- Beel ch’o’ (beel: path and ch’o: mouse “path of the mouse”). Name given by its location, because mice usually walk along the house on this beam.

- Wiinkil che’ (wiinkil: body and che’: wood, tree, “wooden body”). Vertical crossbars that form the body of the cover.

- Jiil Thin rods that are placed horizontally over the wiinkil che’, the guano (Sabal mexicana Mart.) is inserted in these.

- Áanikaab Long and resistant lianas, that are used to tie the elements.

- Okom mooy (okom: wooden pillar and mooy: back side of the house). Smaller wooden pillars, they limit the access, hold the walls and the apsidal 6 part of the cover.

- Chi’ naj (chi’: edge, naj: house, edge of the house cover). It protects the wall of the inclement weather.

- Jalab che’ (jalab: thin reeds and che’: wood, tree). Horizontal thin crossbars that are placed outside, tied to the okom mooy.

Vernacular landscape shaped by the public well, the stone wall and the Mayan housing. Nunkni, Campeche.

Photography: Aurelio Sánchez, 2015

Author’s collection

This formerly urban cultural landscape is now a Mayan landscape excluded from cities. It is preserved thanks to the identity that its inhabitants grant to the housing structure and the symbolism of the Mayan world view (primarily in each name of the structural elements that constitute its roof and walls).

The representation of the body and elements linked to heaven are present in the Mayan house 7, that unlike other kinds of architecture, this one comes alive with the spirit of its inhabitants 8; therefore demolishing a house, being a living entity, is equal to killing a person in Mayan culture.

Other younger houses show us this millenary splendor, landscape that has been transformed according to the different morphological changes, but has kept the iconic elements of housing, vegetation and stonewalls that has been so sold as the Yucatan urban landscape.

Mayan house with crutches due to deterioration. Santa María, Calkiní, Campeche. Photography: Aurelio Sánchez, 2015 Author’s collection

While we enter the many handcraft or souvenir shops in the city of Merida and see this cultural landscape reproduced in different ways, such as houses with their inhabitants, the stonewalls, the well, the flamboyant tree or the extensive vegetation, we shouldn’t forget that those are just a “souvenirs”, that we take with us or give away as gifts.

The true cultural landscape that we acclaim is sick, its life is shortened.

If we continue to value this landscape as a handcraft rather than a cultural heritage, then the only thing left for us is memory.

One of the current re-interpretations of Mayan housing that incorporates different elements characteristic of its typology. Hobonil, Tzucacab, Yucatan. Photography: Gaspar Segura

REFERENCES

1 Popol Vuh (from k’iche’ words popol: community and vuh: book) is a compendium of legends and stories of the Mayas.

Popol Vuh. Las antiguas historias de los quiché, (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1976).

2 Elementos estructurales verticales de madera.

3 William Folan, Ellen Kintz y Laraine Fletcher, COBA: A Classic Maya Metropolis (New York: Academic Press, 1983).

The term “garden city” refers to an urban settlement scheme created in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century by Ebanezer Howard, who considered an innovative scheme including a large proportion of gardens and public áreas.

4 Construction technique that uses natural elements united by mud.

5 Aurelio Sánchez, “La casa maya contemporánea. Usos, costumbres y configuración espacial,” Revista Península Volumen 1, Número 2 (2006).

6 Semicircular architectural plan.

7 As illustrated on page 48.

8 Aurelio Sánchez, Alejandra García y Amarella Eastmond. “La construcción simbólica, formal y material de la casa maya,” en La casa de los mayas de la península de Yucatán: historias de la maya naj, ed. Aurelio Sánchez y Alejandra García (México: Plaza y Vades – UADY, 2014), 57-86.