The urban landscape of the Mayan cities: a vision from the archaeological heritage

The term “urban landscape”, in the current sense of the word, refers to the result of the combination between the constructions and their surroundings, their gestation andmaterialization, and if that result has been the consequence of a more or less intentional or planned historical development. At present, cities such as Mérida (Yucatán, Mexico) have an Urban Development Department that looks after sustainable planning, respectful of the environment and tending to enhance the best that the city can offer.

In the pre-Columbian Mayan past, we did not know if there was a similar governing body to ensure the adequacy of the spaces, their distribution, the combination of built areas and empty spaces for the city to breathe and respond to the needs of its inhabitants. Neither do we know, although there would undoubtedly be, extensive brigades of maintenance personnel comparable to gardeners, carpenters, builders, restorers, who would maintain the distinctive features of the cities, and the values they represented in each case.

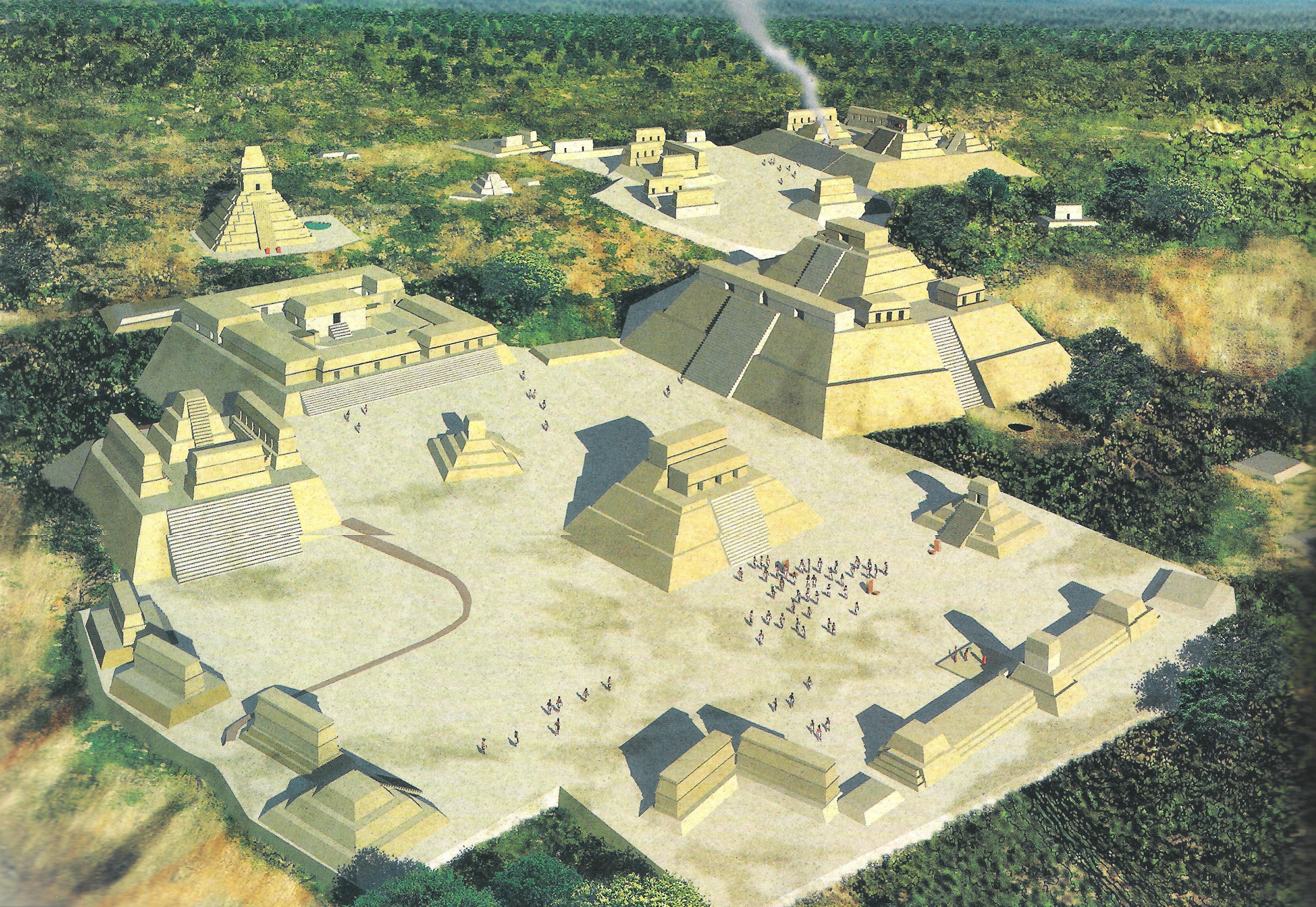

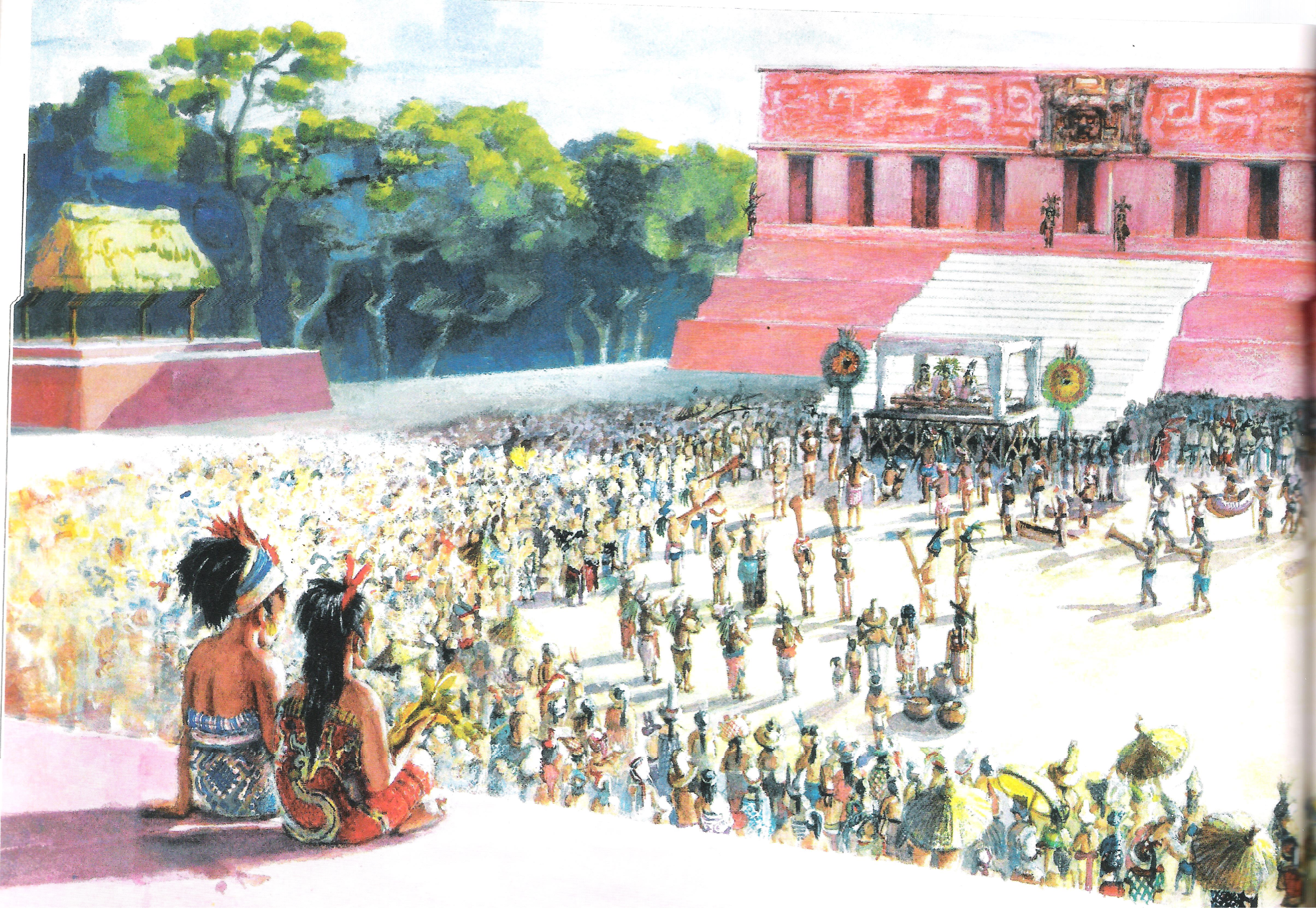

Ideal reconstruction of Holmul (Peten, Guatemala).

Photography: Arqueología Mexicana 137. Enero-Febrero 2016. Página 52

In the pre-Columbian Mayan past, we did not know if there was a similar governing body to ensure the adequacy of the spaces, their distribution, the combination of built areas and empty spaces for the city to breathe and respond to the needs of its inhabitants. Neither do we know, although there would undoubtedly be, extensive brigades of maintenance personnel comparable to gardeners, carpenters, builders, restorers, who would maintain the distinctive features of the cities, and the values they represented in each case.

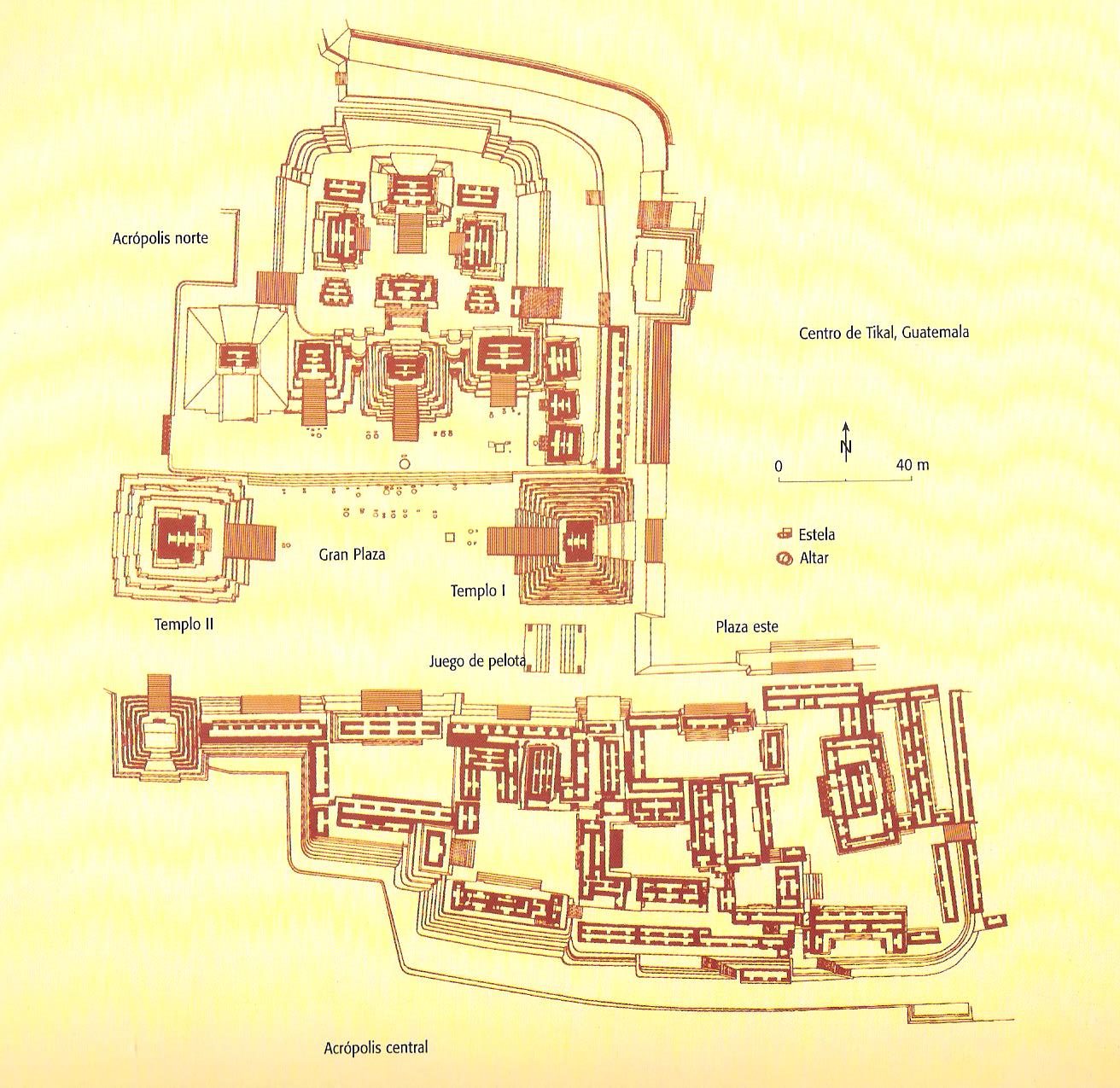

When archaeological maps are visualized, the ideal reconstructions and the material remains of the Mayan cities, doubtlessly many questions are posed about the way of constructing and that planning that would respond to that modern idea of urban landscape, in the city sense, both in the material, as in the ideological, conceptual, economic, religious, among others.

Plan of the Central Acropolis of Tikal (Peten, Guatemala).

Photography: Grube, Nikolai (Ed). Los Mayas. Una civilización milenaria. Editorial Köneman. 2000, página 233

Aerial view of Chichen Itza, Yucatan.

Photography: By dronepicr – Chichen Itza Mexico aerial, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45111006

For a long time, some prestigious archaeologists did not qualify Mayan centers as cities or urban areas in strict sense. The justification for this was the lack of adaptation to the Eurocentric idea of the city as an economic center, a space organized around axes and centers, qualifying Mayan models as only dynastic courts, religious centers or barely more than that. To these justifications were added traits such as the absence of population density, the lack of a powerful productive technology and the lack of means and transport routes comparable. These Mayan centers were, in the end, mere cuts of the classic that competed intensely for taking over the most appetizing areas of natural sources, communication routes, etc.

Mayan cities would undoubtedly respond to the needs of a population integrated in a specific environmental context, with material sources, cultural background and specific social development, without doubt different from other cultures of antiquity. They would agglomerate an endless number of functions of an economic nature as a result of the flows of trade routes that were oriented to satiate aristocratic elites with prestigious materials, whom were eager for these status goods in order to appear before their subjects and peers.

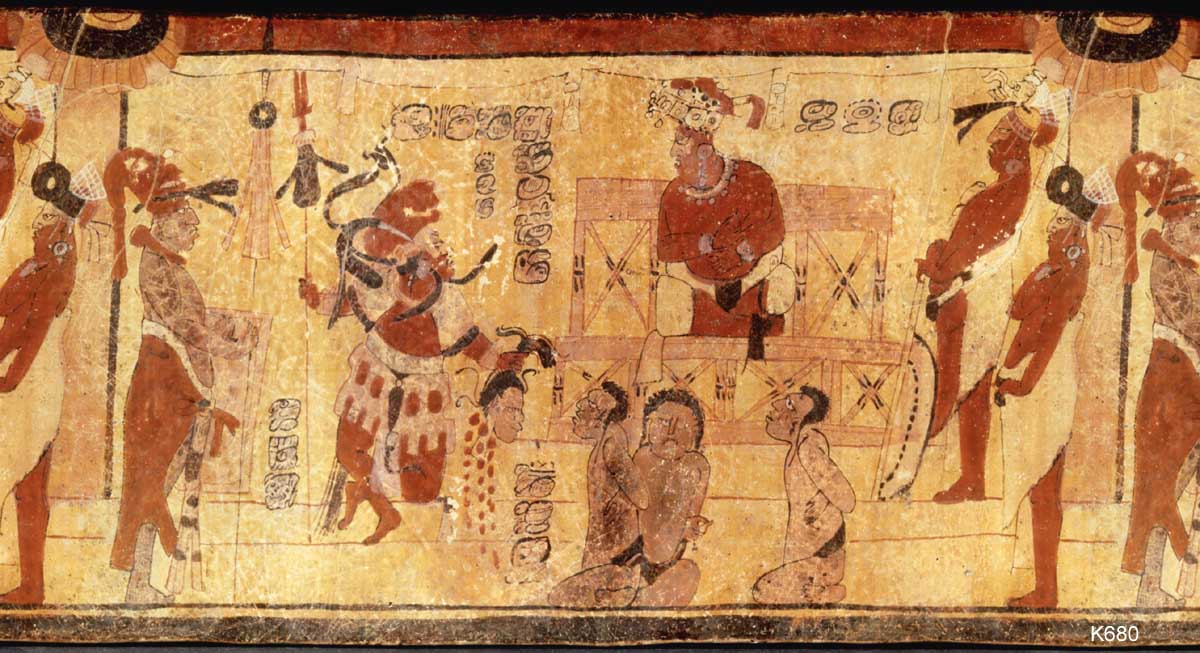

Cylinder vase decorated with palace scene.

Photography: Justin Kerr. Famsi

Also, these cities, currently buried deep in the jungle, were centers of religious nature, but not only during a few dates of the calendar (Figure 4). They were also the center of those power dynasties, enthroned on many occasions as a consequence of war conflicts, which justified their ascension to power based on self-attributed supernatural conditions that allowed them to contact the gods to facilitate the daily life of their fellow citizens and a placid life for them and their relatives.

Recreation of La Blanca’s site center (Peten, Guatemala).

Photography: Arqueología Mexicana 137. Enero-Febrero 2016. Página 60

Palace at Sayil (Yucatan, Mexico)

Photography: Juan García Targa

Those ajaw (political title held by the governing class of the Mayan centers) with its court of advisers, looked for in the ancestors the origin and the justification of its power, and the cult to the ancestors was a fundamental bond since the cities and the centers also served to honor the deceased and make them participants in the lives of those luxurious urban centers of power.

Recreation of a tomb from Calakmul (Campeche, Mexico).

Photography: Juan García Targa

Therefore, the disquisitions about whether the Mayan centers are cities or not seems to me clearly surpassed, and I believe that these cities responded to the daily needs of distribution and staging of power, management of economic surpluses and monitoring of religion and everydayness. The Mayan architects and urbanists dedicated themselves with overwhelming success to give answers to those needs resulting from the conception of the city as a living, changing organism, promoting successive architectural programs alternating constructive volumes of unequal relevance with the plaza spaces, responding to the symbolism of the pyramids as mountains, the presence of caves as the access to the underworld, multiplying the iconographic proposals that gave color and ideological and religious messages to the facades and interiors of the buildings thanks to an excellent craftsmanship.

Undoubtedly, the features described respond to what is usually identified as a city, urban life or urbanism as a will to live together within a certain order, the Mayan one, with no doubt.

I want to dedicate this short article to two good friends and excellent researchers who have left us recently: Jordi Gussinyer Alfonso, Catalan-Mexican archaeologist and architect, who enlightened me during my college years, and Alfonso Lacadena García-Gallo, epigrapher and linguist of recognized international value. My thanks for those good days of conversations, comments, appreciation and laughter.

Juan García Targa. Archaeologist, Barcelona.