Rethinking Water Infrastructure through Territorial Interdependence: The Case of Johads in Rajasthan, India

Aida Tavakoli speaks about the importance of collective and adaptive hydraulic infrastructure, such as the johads in Rajasthan, which integrate local knowledge to care for water and the territory. Learn more about this in Rethinking Water Infrastructure through Territorial Interdependence: The Case of Johads in Rajasthan.

According to the United Nations World Water Development Report, global water withdrawals for domestic, agricultural, and industrial purposes have increased more than sixfold since the early 20th century. Today, over two billion people experience water scarcity each year, a figure projected to reach five billion by 2050. The World Meteorological Organization further highlights that in 2023, global river flows experienced their most severe drought in three decades, jeopardizing the water security of 3.6 billion individuals. These alarming figures reveal not only the technical dimensions of the water crisis but its deep entanglement with sociopolitical structures and infrastructural paradigms.

This article builds on the hypothesis that certain infrastructures, when conceived as sensitive extensions of the territory, can foster interdependent relationships between humans and non-humans, contributing to the sustainability of water cycles. This requires a shift in perspective: hydraulic infrastructure must be understood not only through its engineering function, but also as a mirror of political, epistemological, and ontological worldviews.

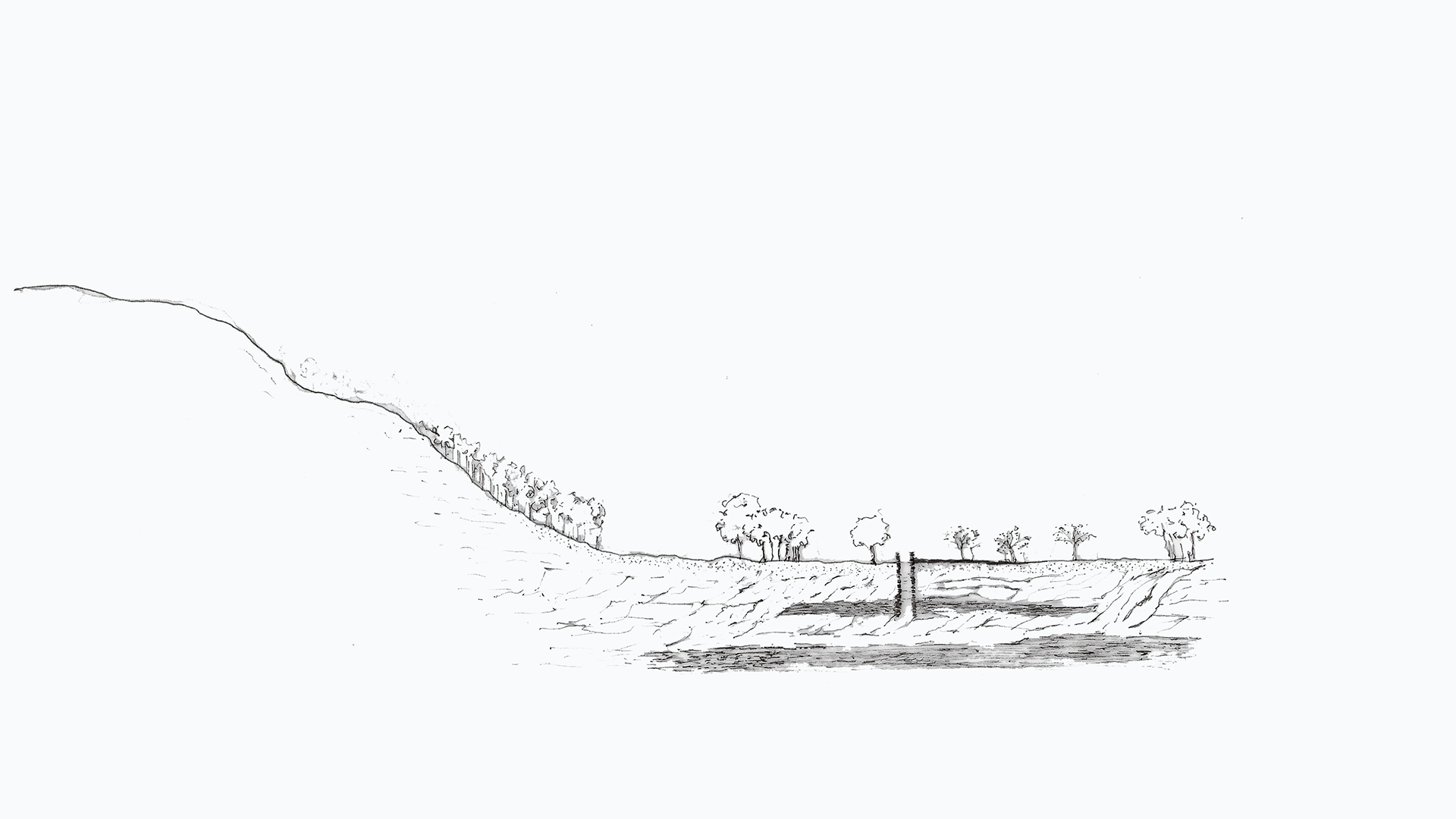

Pozo seco, dibujo esquemático / Dried-up well, schematic drawing

Fotografía / Photography: Aida Tavakoli

The Indian context offers a particularly telling case. Throughout the 20th century, India embraced a modernist hydraulic model rooted in colonial engineering—centralized, growth-oriented, and indifferent to the ecological diversity of its vast territory. The proliferation of large dams, irrigation canals, and electric pumps has led to alarming consequences: aquifer depletion, river desiccation, land subsidence, and social inequality. This infrastructural vision, determined by water demand rather than territorial supply, continues to dominate despite its failures.

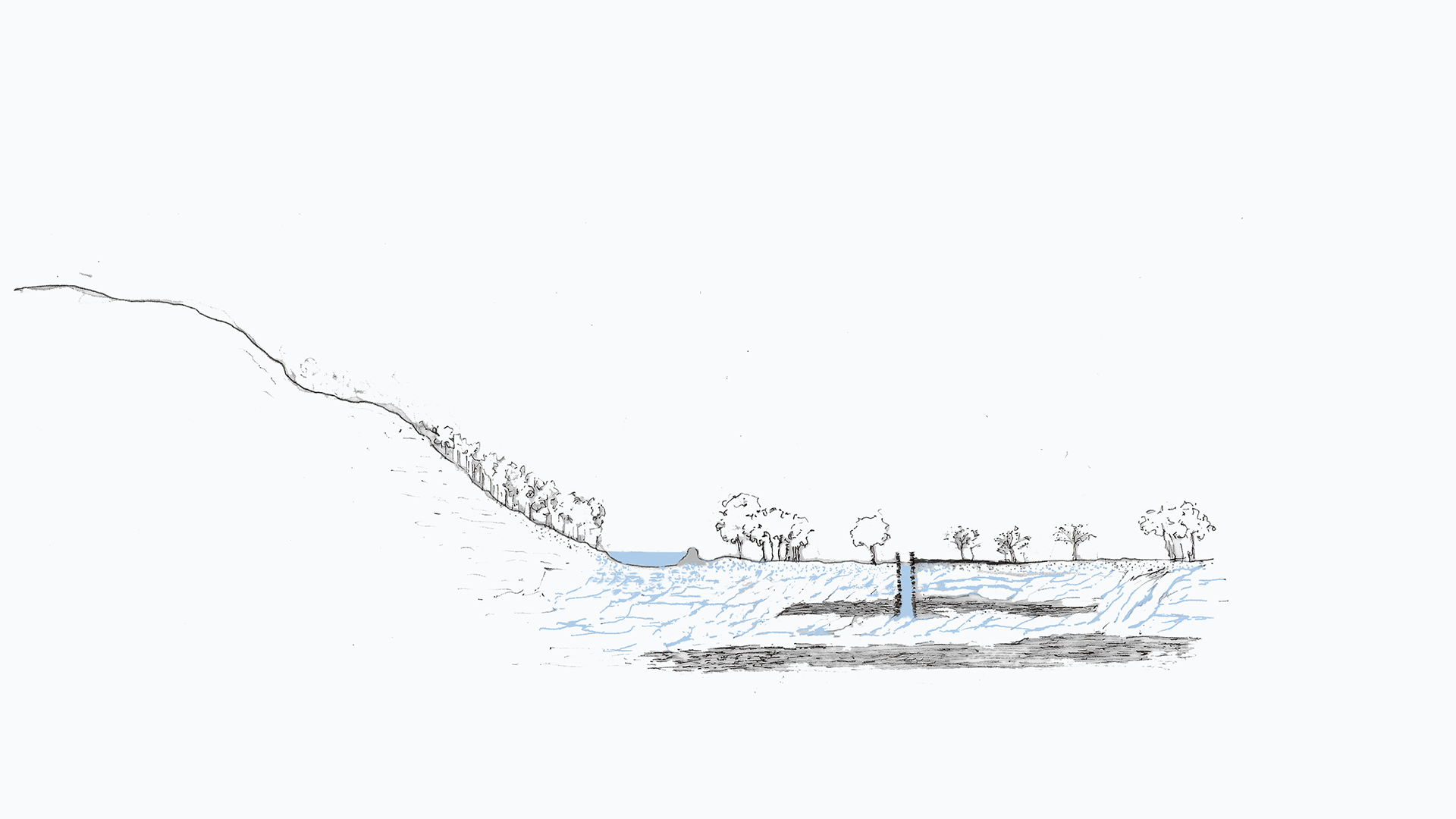

Pozo recargado mediante la instalación de un johad / Well replenished through the installation of a johad

Fotografía / Photography: Aida Tavakoli

In contrast, traditional systems such as johads offer an alternative logic. During fieldwork in October 2024, a meeting with Rajendra Singh, known as the “Waterman of India”, revealed the effectiveness of these earthen rainwater harvesting structures. Johads, typically 50–300 meters long and 30–100 meters wide, are shallow basins that collect monsoon rains and facilitate gradual groundwater recharge. Their design is deceptively simple, but their deployment requires deep territorial knowledge. Functioning as networks rather than isolated objects, johads must be precisely positioned according to the local hydromorphology.

This spatial intelligence is co-produced with communities, particularly women, who, through their daily search for water, map the land’s seasonal flows. Their embodied knowledge identifies areas of water stagnation ideal for johad placement. Thus, the true sophistication of this system lies not in its technical complexity but in its territorial intimacy and collective co-production.

The sophistication of water harvesting systems (such as johads) lies not in their technical complexity but in their territorial intimacy and collective co-production.

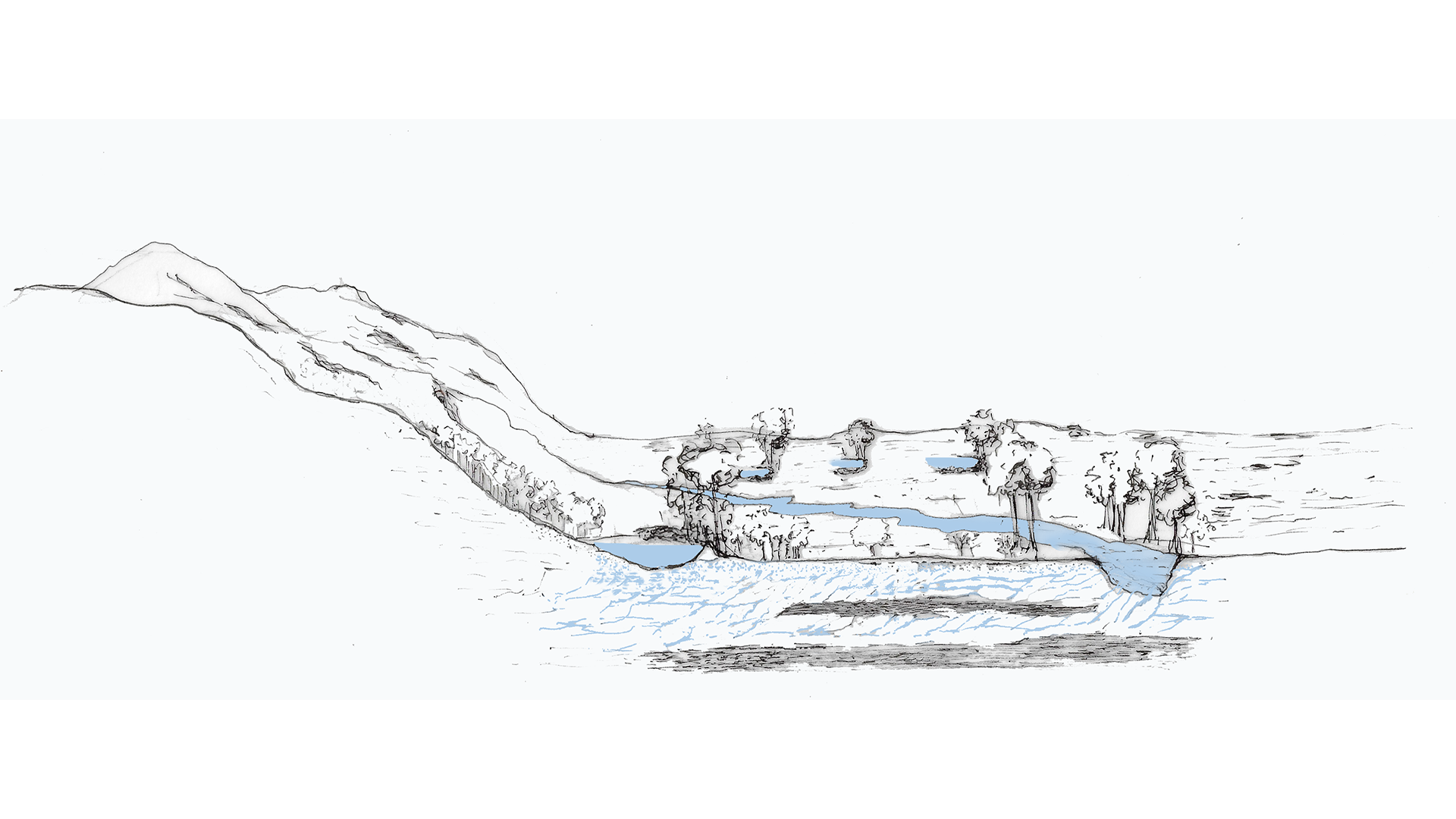

Redes de johads que revitalizan un río/ Networks of johads reviving a river

Fotografía / Photography: Aida Tavakoli

Anupam Mishra, in The Radiant Raindrops of Rajasthan, describes this knowledge as a “popular epistemology of water”: a bodily, ecological, and spatial understanding rooted in everyday life. Over the past 50 years, this decentralized model has generated remarkable results: over 15,800 structures built or restored, 23 rivers revitalized, 1,500 villages reconnected to potable water, agricultural revival, reduced rural exodus, and a restored regional water cycle.

Johads exemplify infrastructure not as an imposition upon the land but as a negotiation with it. They do not seek to overcome scarcity through extraction but work with it, respecting rhythm, fragility, and temporal flow. They embody what could be termed a situated ontology of inhabitation: infrastructure as a threshold space between human and territorial systems, where architecture acts as the operator of relational ordering. Here, form exceeds function; coherence arises from the articulation of human and non-human dynamics rather than from standardization.

Johad en Ghewar, India / Johad in Ghewar, India

Fotografía / Photography: Flickra

In this sense, rethinking infrastructure becomes an ontological act. It involves moving away from fantasies of control and toward an ecology of care, resonance, and mutual adjustment. Infrastructure, then, should be understood not as a finished object but as a living situation, open, adaptive, and rooted in the continuous entanglement of social and ecological processes.