The cosmos garden and the Tlalocan garden: the story of the medicinal garden

To Pedro Camarena, tireless teacher who taught us the value of nature.

To Jacqueline Tapia, friend and travel companion in the search for our culture.

I have memories as a child of my “chichi” (grandmother in Mayan) watering her “matas” (plants). It was a moment of evening peace in the house where they lived, in the outskirts of Merida, Mexico. Epazote for the beans and the bellyache, oregano for the stew, aloe for the burns. Grandmother drew from her plants’ repertoire everything necessary to cure the body and soul, thanks to the alchemy performed in the kitchen.

I found in all that daily ritual, between the garden and the pot, great beauty. A kind of perfect organization between the hours of the day and the spaces devoted to the various family activities. The Greek etymology cosmos refers to the order of things, equally characterized by its beauty. The notion has the implicit characteristic of harmony, which is presented to the observer by means of a revelation (Picon, 2013, p.70).

The domestic garden, and in particular the aromatic-medicinal garden, has indeed this characteristic centrality in the life of the Mayan people, as well as for many other civilizations. Below, we propose to take a brief tour of some of the gardens and iconic botanical collections in some historical sources, with the aim of re-qualifying the garden in holistic terms.

Augustinian Convent of the Transfiguration, 16th century

(Cloister) and Parroquia del Divino Salvador, Mexico

Photography: CatedraleseIglesias_CathedralsandChurches, CCBY2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The ancestral practice of the medicinal use of plants has been part of human culture since very early prehistoric times. About its study and documentation there are some references to ancient writings. According to Mar Rey Bueno, the Ebers papyrus, written approximately 3500 years ago and found in the city of Luxor in Egypt, described approximately one hundred and fifty plants used for healing purposes (Rey Bueno, 2010, p. 15)

Likewise, the first Western studies dedicated exclusively to the plant world are attributed to the Greek Theophrastus (372-288 B.C.), a disciple of Aristotle. However, for the study of medicinal flora, two works are essential. The first is Naturalis Historia by the Roman Pliny “the Old” (23-79), who devoted half of his encyclopedia to species used in medicine. The second, published in the year 78, is De Materia Medica, written by the Greek military surgeon Dioscórides, who described a good number of specimens based on his experiences as part of Nero’s army. (Ibid. p. 17)

On the other hand, in various confines of the world, medicinal practices have been more widely studied thanks to the discipline of ethnobotany, a branch of science that studies human groups, their plant environment and the interactions between them.

Augustinian Convent of the Transfiguration, 16th century

(Cloister) and Parroquia del Divino Salvador, Mexico

Photography: CatedraleseIglesias_CathedralsandChurches, CCBY 2.0

via Wikimedia Commons

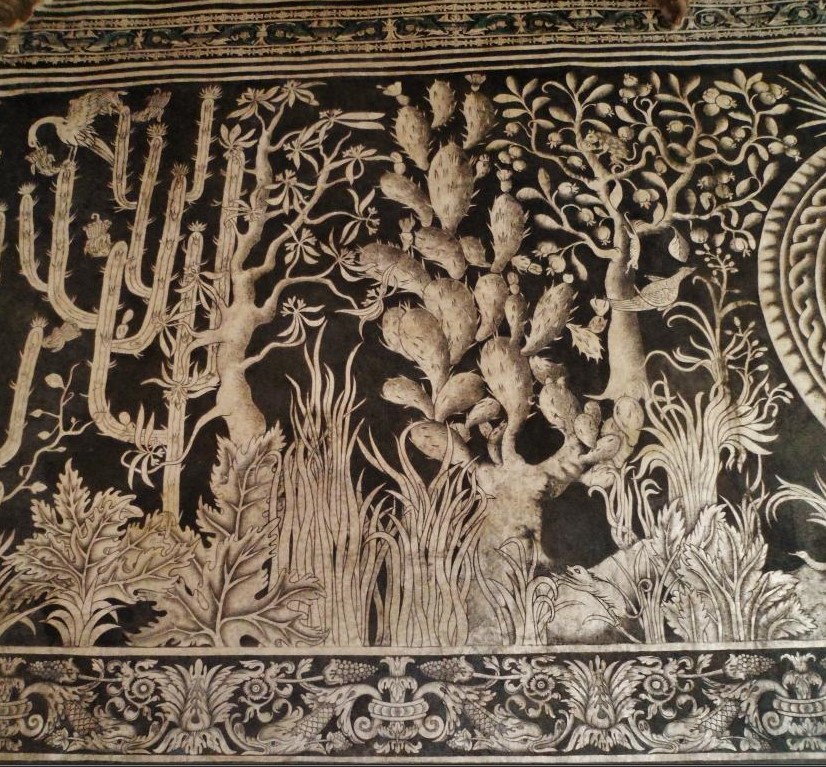

Thus, for example, Carmen Zepeda and Laura White determined that in the murals of the Augustinian convent of San Cristobal in Malinalco, various medicinal plants known to pre-Hispanic people were represented in the murals (Zepeda and White, 2008). In the pre-Columbian world, medicine developed from a particular worldview.

Diseases were the result of the loss of the body’s balance, coming from the supernatural forces of the underworld and the superworld. In this worldview, medicine was dedicated to help the sick recover the lost balance, and medicinal plants were the most helpful elements to achieve the desired effect (Lozoya 1998 cited in Zepeda and White, 2008).

Such knowledge was probably associated with the gardens and plant collections that pre-hispanic civilizations developed. One of the best known and studied examples has been the Nezahualcoyotl and Moctezuma II gardens. The first, built on the hill of Tecotzingo, a palace complex. This operation involved wise men, architects, artisans, magicians and gardeners, who, inspired by the Tlalocan, would make some of the most remarkable landscapes of the time.

Nezahualcoyotl greenhouse in the archaeological zone of Baños de Nezahualcoyotl

in Texcoco, State of Mexico

Photography: Misaelos, CCBY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

According to Alfredo López-Austin this conception of the Tlalocan would represent “the origin and destiny of man”, a mythical place associated with the water god Tlaloc (Medina 2011, p. 68-74). As for Moctezuma II, emperor of Tenochtitlan at the arrival of the Spaniards, he had gardens and bird collections that strongly impressed the Europeans. Bernal Díaz del Castillo related the sumptuousness of these spaces: “Let’s not forget the flower and scented tree gardens, and the many types of them that Moctezuma had (…) and the diversity of small birds that grew on the trees, and the medicinal herbs and the benefits they had were something to behold (…)” (Alcántara Onofre 2014, p. 10).

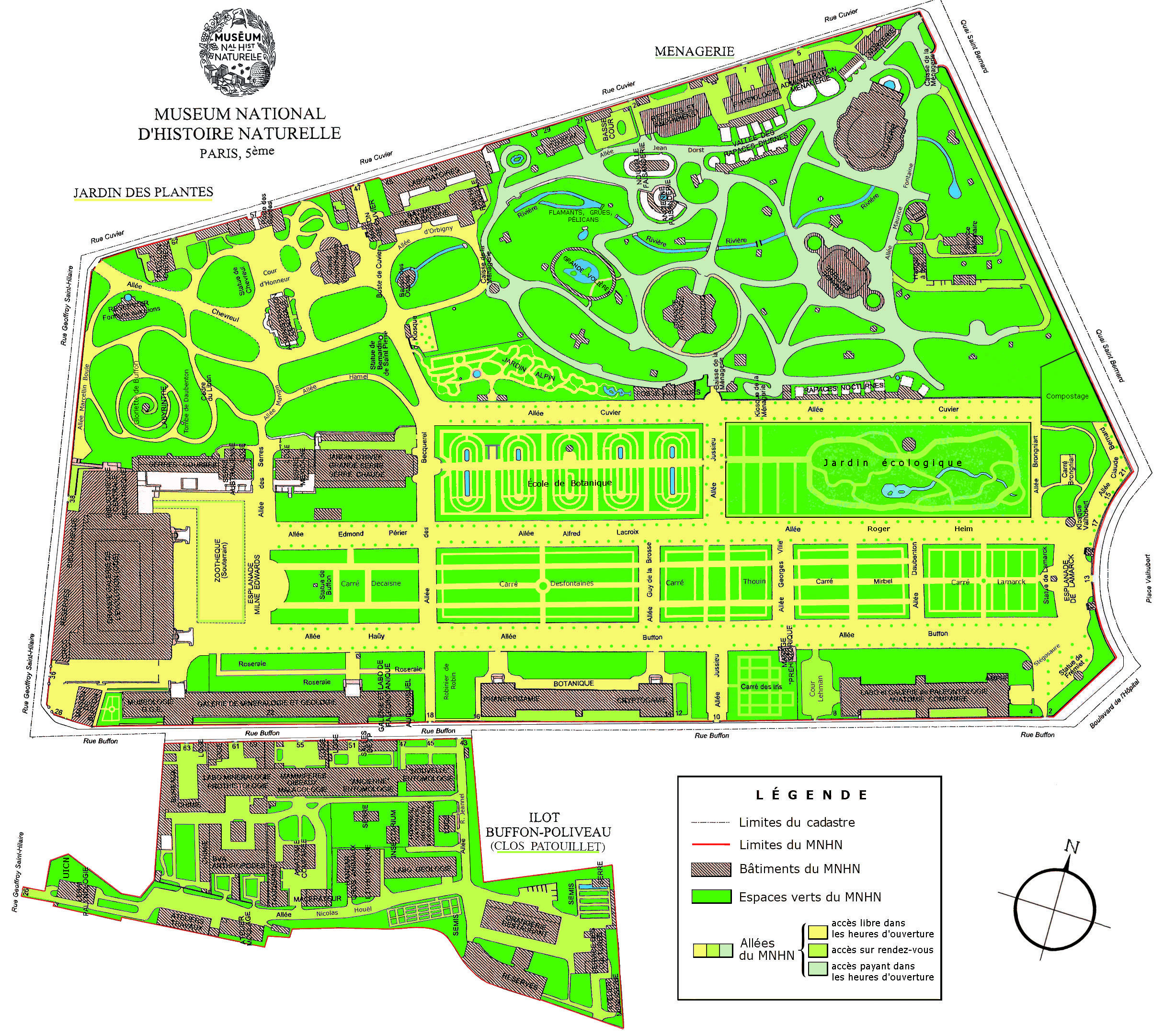

On the other side of the Atlantic, the Western Renaissance was flourishing, taking up again the philosophical and scientific principles of the Greco-Roman antiquity. Under this spirit of renewal, in 1635, the Royal Garden of Medicinal Plants was created. It was created by King Louis XIII, thanks to the influence of his physician Guy de La Brosse.

After five years of work and the necessary planting, the garden was opened to the public. It was a significant success, offering free, accessible scientific education in French, while all other establishments only offered courses in Latin (MNHN).

Detailed plan of the MNHN-Jardin des Plantes

Illustration: SpiridonIon Cepleanu, CCBY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Many other examples of medicinal botanical collections have undoubtedly followed in the world since then. In our days, pharmacological science and medicine in general have focused on producing in laboratories the molecules that are capable of relieving certain ailments. However, what about the ability of human beings to seek well-being by ingesting certain plants, to prevent diseases by improving our diet, as well as the well-being that comes from contact with and care for nature?

Today, the garden –and not only the medicinal kind– constitutes a cosmos in itself capable of providing us with physical and mental balance. As an example of this, gardening practices are multiplying not only in homes, but also in psychiatric hospitals, retirement homes, schools and offices, showing that the garden constitutes an infinite source of wisdom, nutrients and peace of mind. Perhaps if we provide it with all those qualities, we could once again position it as a sacred space in our lives, a reminder that our origin and destiny as humanity is inexorably linked to nature.

Medicinal plants

Photography: annawaldl – Pixabay