Alhambra’s Irrigation System

Using water to a greater or lesser extent, allows to generate landscapes of different entities, therefore the availability of this element is fundamental to create spaces that include intentional irrigation systems.

I am referring to the existence of lands that are watered to multiply the agricultural wealth, meaning that it is an irrigated agroecosystem that achieves what naturally does not occur in the Mediterranean world: to unite heat and humidity, where water is supplied to the fields in the months of drought, which is a characteristic of this weather.

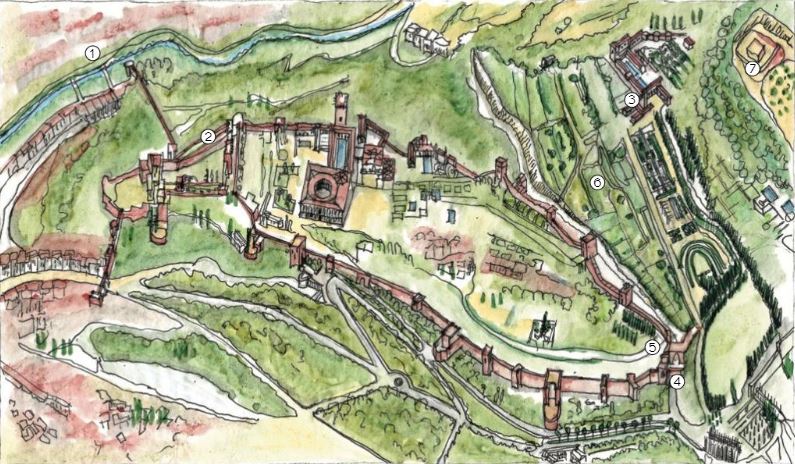

That said, I wish to talk about water in a double sense because Alhambra de Granada is a special scenery, a palace-city created mainly during the nazari period (13th to 15th centuries), but with previous structures 1.

Indeed, in the westernmost part of the hill, in its prow, which occupies the plain that became Vega, over the Darro River, a fortress was built in taifa zirí times (11th century), of which its architectural remains are still visible, especially in the Alcazaba’s (citadel) north facade.

The Alcazaba (citadel) of Alhambra. Photography: By Jebulon – Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21952304

It had a system of water provisioning. A coracha, a part of the city wall that descends to a tower next to the Darro River. Important remains are still visible, known as the Puente del Cadí, which is actually the Puerta de la Compuerta (Gate of the Floodgate).

It used to close to hold the waters so the people and animals could get to the fortress. The restructuration of this defensive structure did not destroy its presence but did modify it.

It was a system that remained in use, or at least it could be used. Later on, the city – palace was provided with defensive spaces and separation mechanisms for the military control that was necessary. When these structures were added, the water that reached the Alhambra complex also was directed to the Alcazaba (citadel) through an extension of the water channel.

Photography: legadonazari.blogspot.mx

two representations of the original state of the Puerta de la Compuerta (Gate of the Floodgate). Photography: legadonazari.blogspot.mx

The still visible remains of the Puerta de la Compuerta (Gate of the Floodgate). Photography: C.M. “El Descanso de El Coto”

When the first Nasrid king Muhammad I settled in this space, which until then had only been occupied by the Zirí military structure, he had the firm intention of inhabiting much of the hill, the area that descends to the western end.

This desire, mentioned clearly in the written sources, included the strategy of opening a channel from the Darro to the hill . He created an irrigation channel, called Acequia Real or Acequia del Sultán (Royal Water Channel or Sultan’s Water Channel). He made a dam to limit water flow and deviate it to the hillside descending until entering the enclosure.

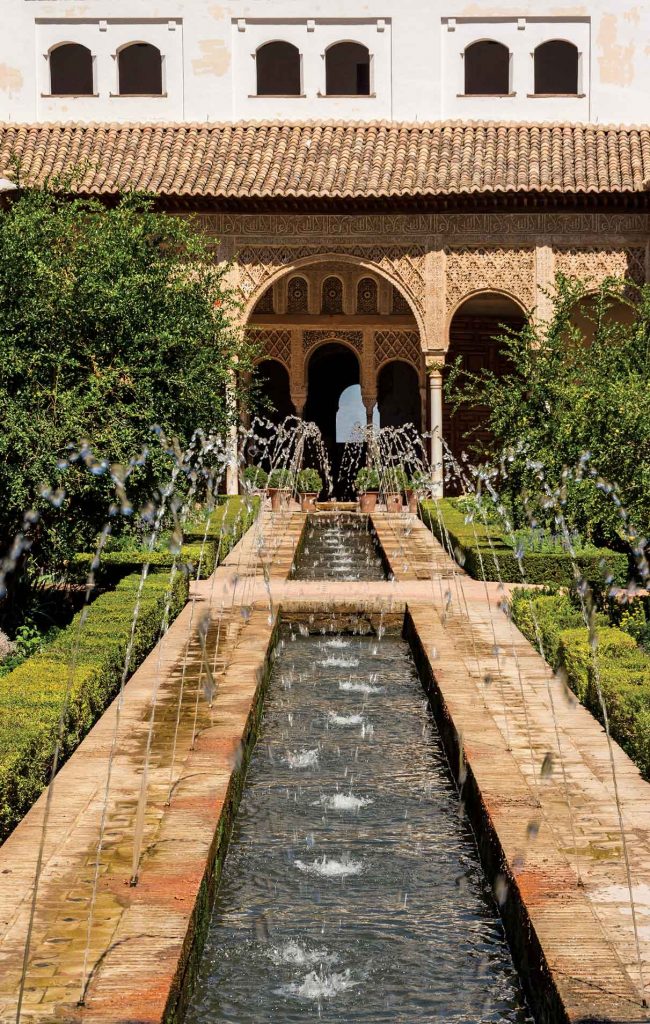

It goes through the Generalife, which is a later work but belongs to the first epoch; more specifically, Muhammad III established the current spaces of the Alhambra. The channel enters the enclosure through Torre del Agua (Water Tower), where the aqueduct conquers a ravine, crosses the summit and spills in both of its sides, generating a very logical urban system. In the middle of its journey it crosses the greater mosque, which differentiates urban space from the palace.

Fotografía: Jebulon, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Patio_de_la_Acequia_Generalife_1_Grenade.jpg

Photography: Jebulon – Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21807616

Water becomes the quintessential vivifying element in both urban and vegetation areas, in gardens and orchards that embellish the whole ensemble and its surroundings. Therefore Alahambra and Generalife define areas where vegetable life must be viewed not only as an ornament but considered also for its substantial productive capacity. The best examples are the orchards located under Generalife that should be considered as a farm.

The agricultural life, usually forgotten by the palace’s academics, viewed the water as an element for agricultural production, and this conception would have a fundamental role in uniting the decorative and aesthetic elements.

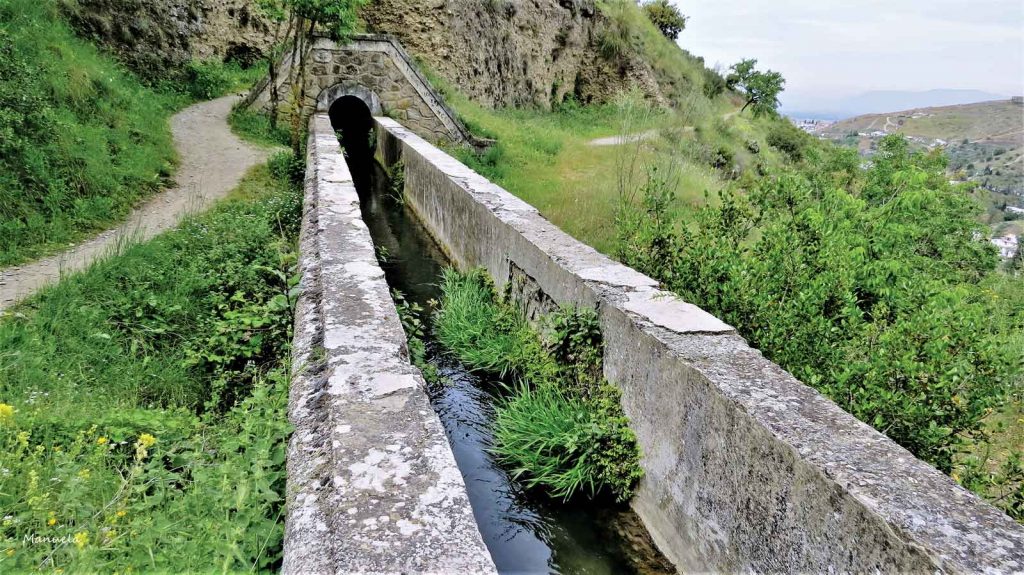

The Sultan’s Water Channel exterior path on the sidehill. Photography: Manuela Fernández Cuesta

Clearly, this double significance of water motivated change on the hydraulic system and its global organization. Thus, there was a significant expansion of it with a view to supplying water to hitherto un-irrigated areas.

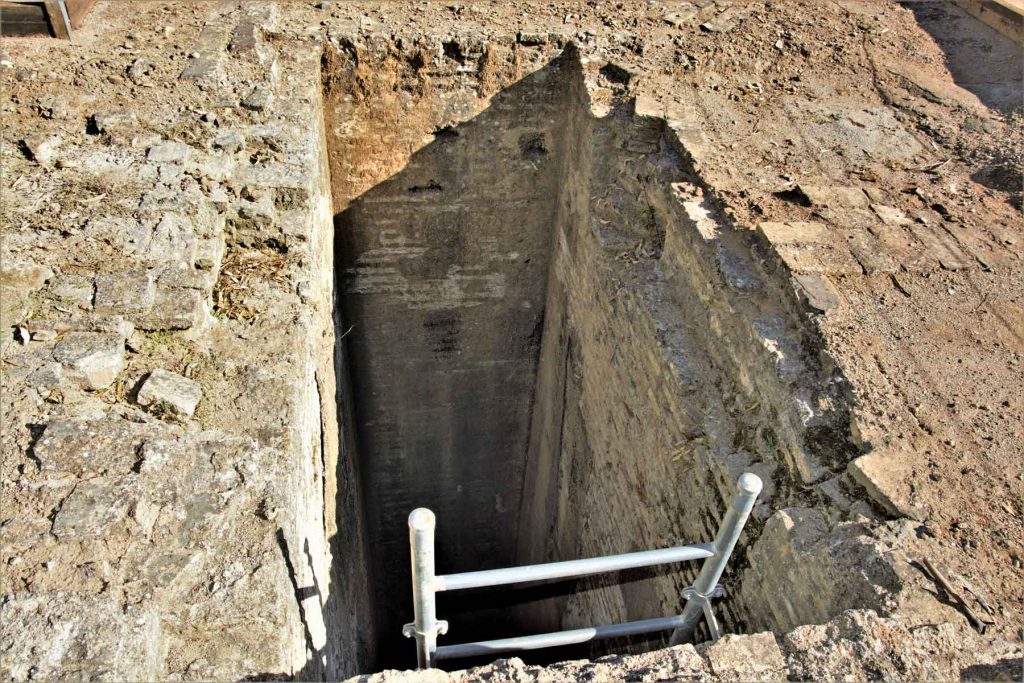

Above the existing orchards, a large albercón (pool) was created and water was conducted through a subterranean gallery that begins at a lower level, generating a negative inclination where water must be elevated using a waterwheel that fills a receptacle and later irrigates the lands that thanks to this system became cultivation areas.

Well with waterweel that brings up the water for the Albercon de las Damas (Ladies’ Large Pool). Photography: Manuela Fernández Cuesta

Albercon de las Damas (Ladies’ Large Pool) situated in the upper part of the Alhambra’s hydraulic system. Photography: Manuela Fernández Cuesta

It was a small expansion, but it would not take long to grow due the unfolding of the Acequia Real or del Sultan (Royal Water Channel or Sultan’s Water Channel). This parabolic expansion on the upper part, that did not exist until then, was called Acequia del Tercio (Water Channel of the Third) and it watered the area that previously was irrigated by the previously mentioned Albercón de las Damas (Ladies’ Large Pool). This transformed the orchards and added value to this space as far as Torres Bermejas 4.

It is an extension that aligns with the growth of irrigated territories that seek a bigger productive capacity, according to the growing demand for agricultural products between the 12th and 13th century during the Almohade Epoch and that prevailed in the next period, the nazarí.

Water shaped the landscape of the hill were Alhambra and Generalife settled, provided life and made it productive. It also generated a scale of aesthetic and economic values. There would be no turning back; its fertility and vital scale were ignited forever.

. Photography: Manuela Fernández Cuesta

1 Para el examen general de la Alhambra y sus estructuras, cfr. Torres Balbás, Leopoldo, La Alhambra y el Generalife, Madrid, 1953.

2 También puede consultarse: Torres Balbás, Leopoldo, «El Puente del Cadí y la Puerta de los Panderos en Granada», Al-Andalus, XIV (1949), pp. 357-364, y Malpica Cuello, Antonio, «Un elemento hidráulico al pie de la Alhambra», Cuadernos de la Alhambra, 29-30 (1993-1994), pp. 77-98. Una referencia en un texto del siglo XII: Al-Zuhri, El mundo en el siglo XII. Estudio de la versión castellana y del “Original”Árabe de uan geografía universal: “El Tratado de al-Zuhri”, Barcelona, 1991, p. 170.

3 Claras referencias textuales en El anónimo de Madrid y Copenhague, traducción de Huici Miranda, Ambrosio, Madrid, 1917, pp. 139-149, e Ibn Idari, Al-Bayan al-Mugrib, traducción de Huici Miranda, Ambrosio, Tetuán, 1954, p. 125.

4 Ana Duarte Rodriguez, The Small Power of ‘Small’ Gardeners during the Great War en Uma Pequena Potência é uma Potência? (Lisboa: Cadernos Instituto da Defesa Nacional, 2015).