Court Square Press

The Court Square Press building was built in 1900 as a printing press on the edge of Boston’s Fort Point Channel district, an area historically used for manufacturing and shipping. The site itself was created during a series of early twentieth century fill operations in which the channel was transformed into rail yards. Originally marking the southernmost reaches of the Boston Wharf Company warehouse development, Court Square Press is now the southern anchor of the Fort Point Channel Activation Plan, an open space master plan by the Boston Redevelopment Authority.

Today, the Court Square Press Building stands in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood near the Broadway T Station in South Boston, Massachusetts. Landworks Studio, in collaboration with John Cunningham Architects, was tasked with transforming the 19,500 m2 industrial building into residential condominiums. Formerly, the surrounding area was characterized by impervious asphalt parking lots, cobble-strewn tracts, and remnants from abandoned railroad and shipping yards. This space not only needed to contain spaces for gatherings of various sizes, but also had to provide an ADA-compliant egress path with adequate lighting and screening for the ground level units.

“The building’s architectural renovation revealed leftover space and inspired the developer with a vision for creating an urban oasis within the building’s six-story central void.”

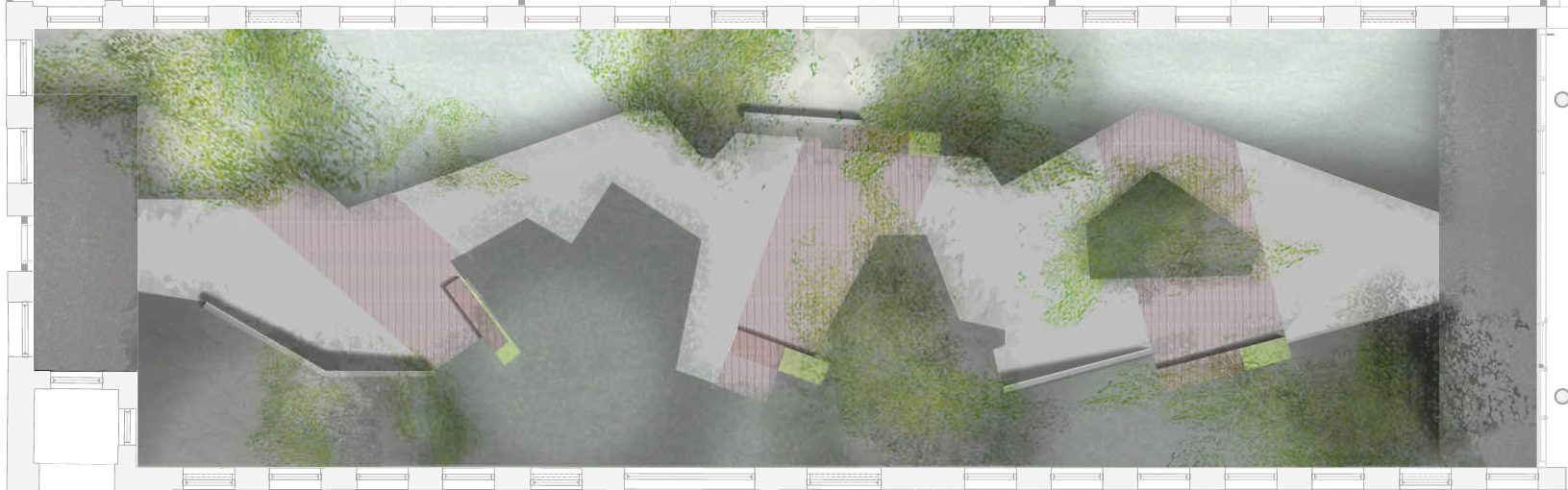

Courtyard rendered plan

Plan: Landworks Studio, Inc.

In response to these requirements, Landworks Studio centered its design on the notion that a cohesive, multipurpose landscape can emerge from fragmented views. In this particular case, the fragmented view is a product of the narrowness and deepness that characterize the 15 m x 61 m courtyard, in combination with the limited visual access into the space that results from the thick brick-and-mortar structure’s small punched windows. Because of the narrowness of the space and the extremity of its height, the garden was envisioned as a vertical filter. Since each of the residences offers a distinct view of the courtyard, the variable figuration of path, benches, and plantings embody fragmentation to create a unique scene from each window.

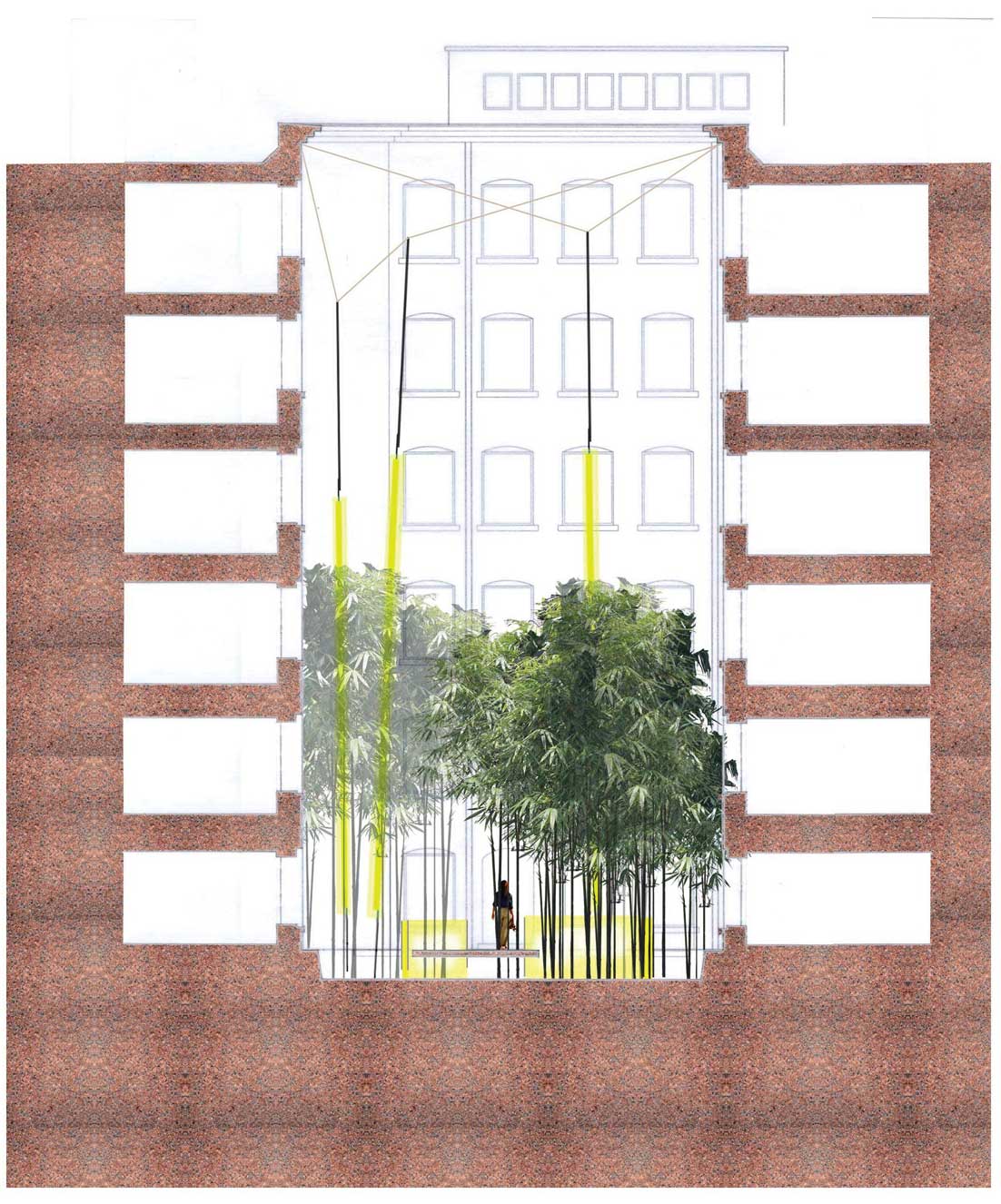

Courtyard rendered section

Plan: Landworks Studio, Inc.

Within the space, a carefully calibrated material palette cultivates visual and spatial diversity to compete with the enormity of the courtyard’s enclosure. Encompassing organic to inert ingredients, coarse to fine textures, and light to dark values, the courtyard is populated by lighted elements, undulating ground planes, a floating deck, and integrated plantings that engage each layer of the garden and create unique moments for visitors. These discrete landscape elements coalesce viscerally into a dynamic garden whose fragmented views emerge into a unified whole as one moves through the space.

The pre-existing condition of the courtyard

Photography: Landworks Studio, Inc.

The intense variability of the courtyard’s design also has the benefit of providing a measure of privacy to the ground floor residences. While at lower levels, the use of dense ground covers such as Lilyturf and Marginal Shield Fern, lighted benches, and topographic undulation creates variation and alternation, the density and layering of these materials also limits how close people in the courtyard can come to the ground floor units and obscures the view from unit to unit across the courtyard—a feature that will only increase as the bamboo matures.

View across courtyard

Photography: Landworks Studio, Inc.

When seen from above, the dense, asymmetrical layers give each unit’s owner the sense that he is looking over his own private garden—thus subtly enhancing property value, contributing to a greater sense of place, and furthering the seamless value of semi-public outdoor spaces within a larger urban landscape.

Because the garden is conceptualized as a collection of fragmented views, it follows that the lighting strategy should avoid any sense of compositional or figural completeness. The building’s massive brick wall is perforated by an unrelenting six-story grid of windows that introduce ambient light into the garden. At nighttime and on dark winter afternoons, the courtyard’s lighting strategy is intended to be in direct dialogue with the adjacent residences: because of the courtyard’s east/west orientation, indirect sunlight reflects off the regularized glazing pattern and illuminates the courtyard floor. These reflected trapezoids of light temporarily reveal the garden’s contours and articulate the walkway’s alternating wood and metal surface.

View of middle section

Photography: Landworks Studio, Inc.

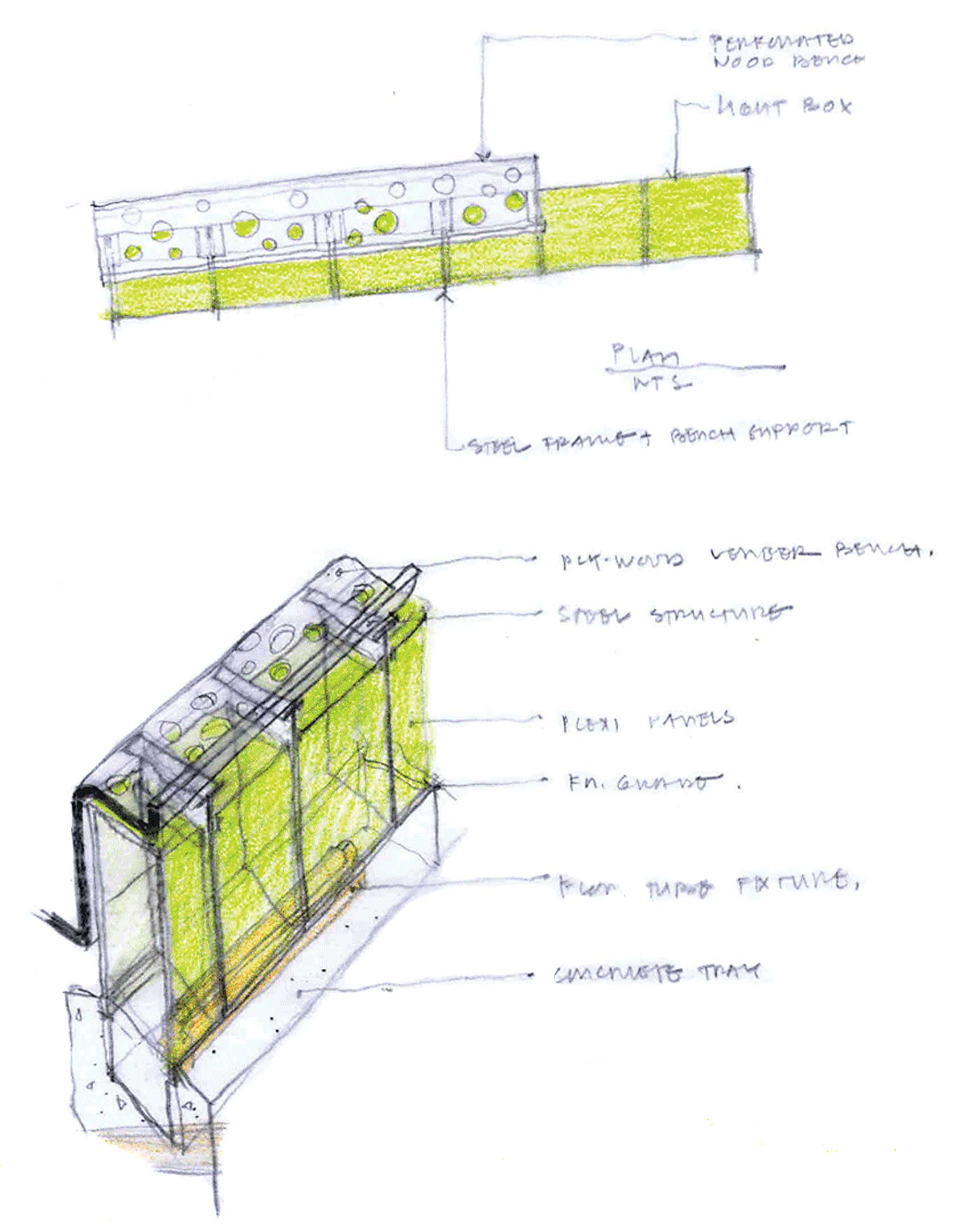

The courtyard’s artificial lighting interprets light as a continuous surface—through luminous Lexan benches that bring the wood panels, steel decking and planted areas along the path into stark contrast. These lighted benches, in combination with overhead lighting, also give rhythm to the path’s zigzags, their patterns suggesting an electronic version of the garden’s subtle bamboo motif, thus weaving together natural and artificial layers.

Luminous bench design

Photography: Landworks Studio, Inc.

Detail view of bench

Photography: Landworks Studio, Inc.

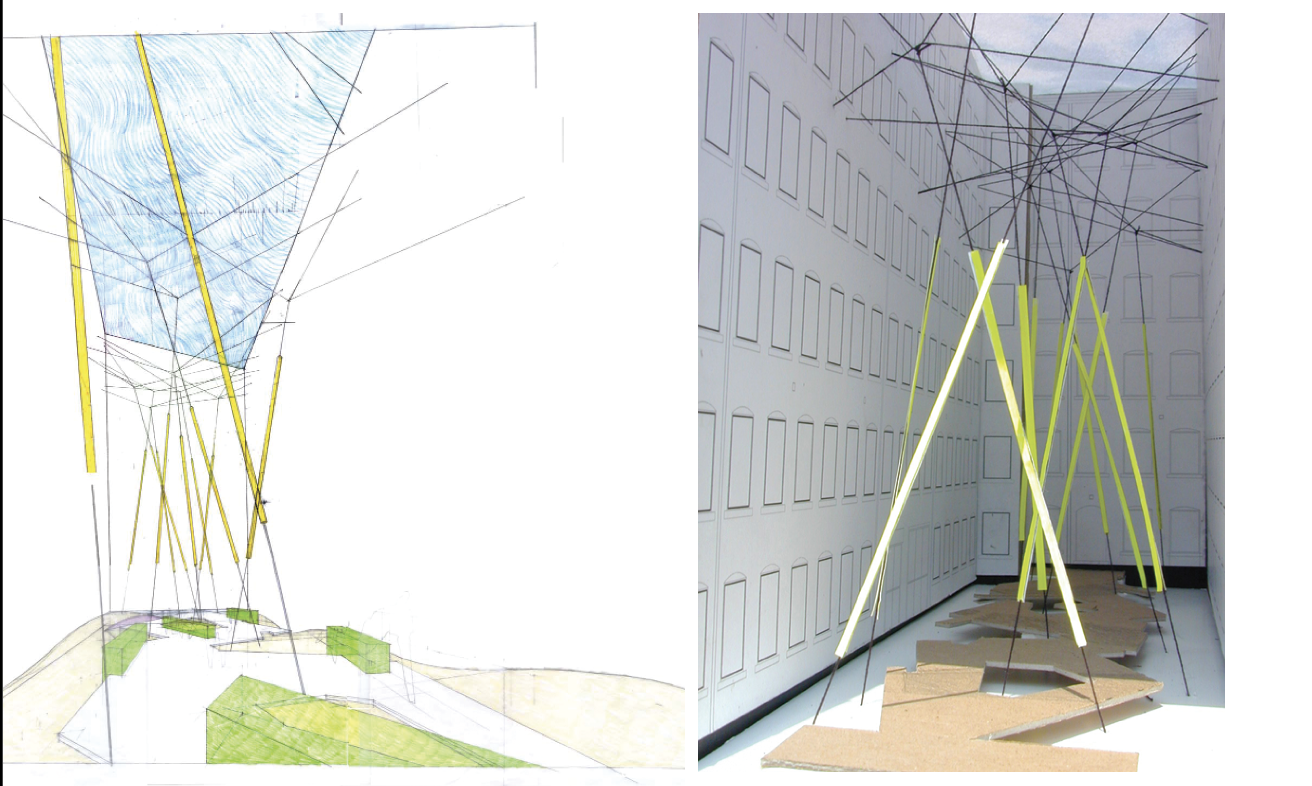

Elsewhere, the bamboo motif comes alive, with Yellow Grove and Nude Sheath bamboos creating the primary canopy textures, while an intermingled web of suspended yellow fiber optics and taut steel cables provide visual continuity between the backdrop of bamboo and the foregrounded benches.

These fiber optic lines levitate between the ground and the building’s cornice, casting colored light into the maturing bamboo canopy. As a result, residents at the upper levels, while deprived of ground level views, still experience the fragmented visual play between light, stainless steel cables, and bamboo branches. By day, the patterned structural web system and bamboo casts an interesting complex of lines and shadows onto the hardscape. By night, the web-structure recedes and the thicket of lights emerges as a floating system within the grove of bamboo.

1. Sketch of the fiber optic web-structure

2. Early concept model

By: Landworks Studio, Inc.

From a social standpoint, the asymmetrical disposition of objects in the space generates an interesting variety of movements and a range of gathering spaces. Oversized and rotated benches create asymmetrical relationships with both the building envelope and the undulating ground plane,

creating various gathering spaces. Framed by the lighted benches, the courtyard’s deck areas give subtle cues to different types of usage based on the material underfoot: either Ipe wood or aluminum decking. These spaces remain flexible, however, to accommodate the changing character of the space at the end of the day and into the evening, as various neighbors and visitors occupy the same space, amplifying the sense of community. Much like campers around a bonfire, people gather around the lighted benches to converse, tell stories, and linger in the illuminated bamboo forest.

View of finished courtyard at night

Photography: Landworks Studio, Inc.