As disruptive as Alexander von Humboldt

Preparing that great journey to a new place unknown to our senses is something intimate to many of us… What should I bring with me? How many kilos should my suitcase weigh? Will the weather be cloudy or sunny? These are the most common questions that run through our minds, and that fill the reminders on our phones and the conversations with coffee in front of our best listeners. Preparing a trip immediately turns us into explorers because we begin to imagine, question or even formulate theories about the strange.

Explorer

Photography: www.pixabay.com

Torres del Paine

Photography: Pixabay

I remember my first very moment as an explorer in a new great place (Torres del Paine). I felt like a giant at every step in the path and at the same time, I felt like an ant before the crown of Nothofagus pumilio. Sometimes I felt afraid before the possible appearance of a Puma concolor, others, I felt the singular joy of being able to drink water from the fall of a fine waterfall after a long non-stop journey, so I now question you… Have you ever shed sweet tears in the face of having achieved an enormous physical effort, accompanied by an unrepeatable postcard? Well, Alexander von Humboldt did, as I am informed, he cried at the top of Chimborazo when he proclaimed himself one of the few explorers to climb the highest peak in the world discovered up to that moment (late 18th century). Which of all those tears shed in Ecuador was dedicated to the multiplicity of elements expressed in a path? Which of those animals and insects made him feel the same fear I felt with the puma? The first answer, all of them. The second answer, mosquitoes. According to Humboldt, no matter the size of the threat, all of them can be overcome if we read the landscape that nourishes us. And so, he won another title: the one of being the first interested in developing a new concept of nature and, although a little rugged, the pre-concept of landscape.

Alexander Humboldt

Photography: www.pixabay.com

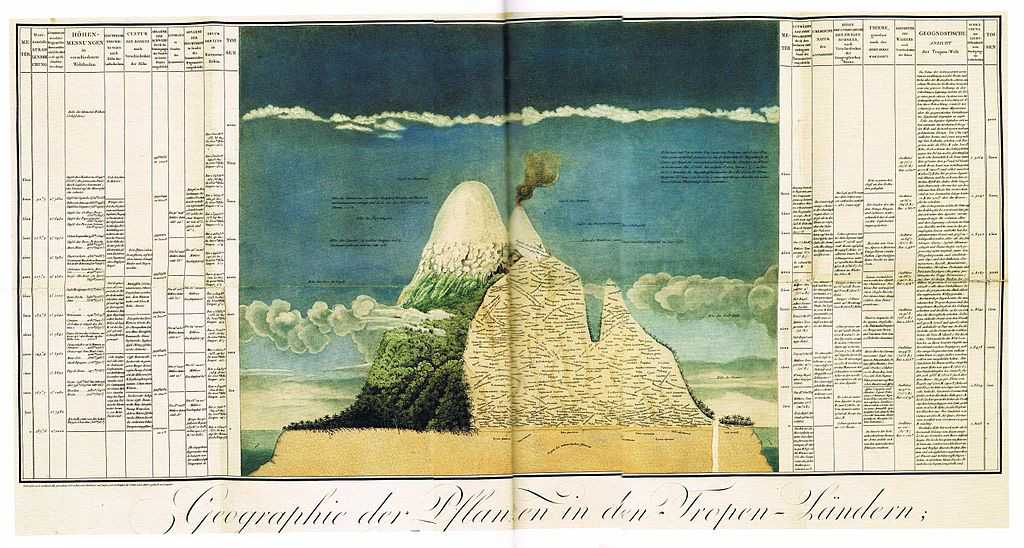

Naturgemalde

Photography: Wikimedia

Let’s place ourselves in the mind of a 27-year-old Humboldt who documented his great journey in the book Personal Narrative, telling the wonders of witnessing the how and when of those layers that were so important for the environment. He understood that everything is linked, that we are all part of a great system where everything interacts with each other: the scales of flora, fauna, climate, altimetry, soil, geology, the blue of the sky, clouds, wind, fungi, and feet that hold people like roots to the trunk; and how they project a frontier that either expires, or remains.

“Nature everywhere speaks to man in a voice that is familiar to his soul”

Goethe and Humboldt

The Humboldtdian thought is in our minds in an intuitive way since he has managed to insert himself in the works of multiple scientists, artists, writers, and poets throughout the last 200 years. To speak of landscape-system-nature in a time where the majority of the world’s population thought (and still thinks) of agriculture and livestock as a source of progress and saw the elements around them as inferior.

That Humboldtian thought currently spins around in *insert your favorite news source*, saying that we should see the world as a system and that if we take a piece, it will fragment to the degree of its destruction, like a cannibalism forced by our ego and the enormous lack of empathy, that same empathy Humboldt felt in each and every one of his great journeys when he learned about slavery, hunger, looting, deforestation, erosion, the greatness of wars and the fragmentation of that idea of a system until becoming dust with no return.

UN 2030 Agenda

Humboldt wrote in his book Cosmos that life is made up of so many factors, including empathy, that it took him five volumes to consolidate that assertion before his readers. He was able to inspire with his stories, with his Naturgemalde, with his maps, drawings, and prose. Even Goethe admired him and they inspired each other through their paths.

What would become of Faust if we brought it to the present day? Would it be a Leonardo DiCaprio, bound to spread the errors that Humboldt once read in the landscape?

Reading the landscape, as an obligatory basis for the adsorption of our senses in the face of the system’s transition, just as Humboldt did, should be part of us, according to the social media that want us to wake up and adopt a “green” behavior. But should it really be like this? I inquire it as a disruption over the disruption. How green was Humboldt in his great travels? Do we first understand what we perceive, then we value its existence, and then we try to reverse the damage by being “green”?

My final thought is that we should ask questions: Humboldt’s proposal is that we should be passionate about the answers we get and put them to good use.